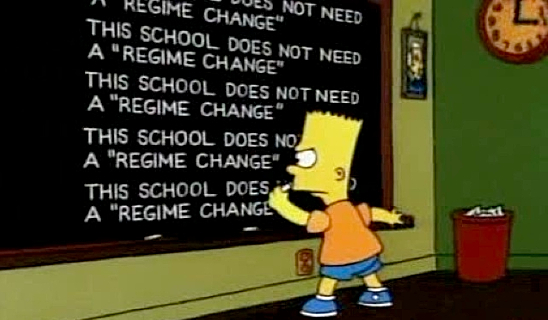

We Need Educational Regime Change in 2014

We need regime change and not in some far away land, in which a wayward dictator threatens our oil supply. We need regime change in education. Regimes are not just groups of people – despotic politicians, kleptomaniac ruling families, corrupt military junta – who hold onto power in defiance of the public will.

Regimes are even more powerful when they are impersonal, embedded in routines, hidden in norms, conveyed in rules, which govern what people do, shape how they think and provide the justification for their actions. Regimes of this kind condition what we regard as feasible. They orchestrate business as usual. They lack a single conductor. They come to seem logical, the natural order, even though they are only recently invented.

Educational Regimes

In education the regime that defines what should and could be done is deeply entrenched in the school and the lesson, the curriculum and the test, the timetable and the year group. The regime is not loved but at least it is familiar and seems safe, despite its evident and growing shortcomings. Better the devil you know. This regime’s power comes from having made itself common sense.

Education has become an increasingly sophisticated sorting system for young people who come round like the parcels on a carousel at a UPS warehouse, waiting to be picked, scanned and delivered to the destination the system has decided for them. The point is not to excite imagination, encourage creativity, build self-reliance, form character, learn self-governance, forge willpower, strengthen resilience or find leaders.

The most powerful lessons children learn at school are not what they are taught but what they learn about life and themselves through their experience of the process of schooling and the culture it creates. Children learn that they can be enthusiastic, punctual, diligent, neat, hardworking, get good grades and yet still be bored witless because learning is neither absorbing, challenging nor energising.

Schooling systematically underestimates the children it teaches and worse teaches them to underestimate themselves. Many enter the system full of hope and leave deeply disenchanted, wanting nothing more to do with it. If “Do No Harm” were the key design principle for an education system then the one we have devised would count as an abject failure. It harms children everyday, by the way it spreads and multiplies failure.

Effecting Change

Yet regimes do change. They change when many people, with overlapping and different causes, come together to create a coalition, which coalesces around a new approach. Often the decisive factor is that regime’s fracture from within, losing critical support from key groups like business, as well as facing mounting popular pressure from without.

These movements for change often coalesce around a new technology or way of doing things. That is what is really at stake in the debate over the potentially disruptive role of technology in learning. Does it create the possibility of a new regime, not just new tools and services, which help to rationalise and systematise the current regime even further?

The best learning in the future might be a mixture of the very new – digital technologies – and the very old – almost pre-industrial models of learning, as work, debate, argument, service. As we search for a better way to articulate what this different kind of digital learning might be like our best guide is likely to be quite old fashioned. If we modeled more learning on music, for example, then we would go a long way to making education both inspiring, challenging and demanding.

A Personal Example

My 14-year old son is lucky enough to go to a brilliant state (public) school just down the road from where we live in north London: Highbury Grove Comprehensive School. Music is at the heart of the school. Every child has a musical instrument. Any child who wants a music lesson can have one. Almost all the children are learning a musical instrument and the vast majority take part in some kind of music group. What do they learn by music being the common currency of the school?

Learning a musical instrument requires constant practice, effort and discipline. Basic technique has to be mastered. There are no short cuts. Formal systems of notation have to be learned like a formal language. Yet much of the knowledge of how to play is not in the head but embodied in fingers, arms and legs. Butterflies have to be controlled for even the smallest of performances. Of course there are grades to be passed, exams to be studied for; but children learn also by playing in concerts and giving performances.

Playing in a group, ensemble or orchestra teaches you how to be part of something larger, to play your part, to support one another and to take your cues from other players. Instruments have to be looked after and protected; they cannot be tossed around. Not a single instrument at Highbury Grove has ever been vandalised or stolen.

Learning an instrument and playing it with others, engages virtually every aspect of who we are, from head and hand, to imagination and feeling, yet it also requires discipline and persistence. In short learning a musical instrument is an investment in your own creativity and character.

We Need Change Now

Education has to reclaim its sense of purpose and the belief that it stands for something more than getting good grades. It has to persuade people to invest in it, not just financially but emotionally, because it builds character and helps people to lead more successful lives. It has to dare to stand for something more than the pieces of paper it hands out to children as they leave.

If we were to model all learning – maths, chemistry, languages, technology – on the kind of holistic experience of learning to play a musical instrument, then we would have an education system that engaged mind and body, which was simultaneously systematic and expressive, personal and social. It is that kind of idea that we need to put at the heart of the new kinds of education we need, rather than the particular tools and technologies, whether those be violins or computers.

Charles Leadbeater is author of We-Think: mass innovation not mass production and Learning from the Extremes.