Deep Thoughts or Deep Prejudices?

Are Google and other websites rewiring our brains? Do the potentially distracting non-linear structures of new media pose a threat to ‘deep’ thought, contemplation and even empathy? This is Nicholas Carr’s argument in his book, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains.

Carr argues that there is a good fit between the way ideas develop along a linear path in books, and the way in which human memory works. This match makes possible a certain ‘deep’ style of reading and thinking, Carr claims, while the non-linear designs of the Net and eBooks are not so well suited to human patterns of thinking. New media structures tend to overtax the limitations of human working memory, he argues, in that they offer a surfeit of information, leaving users stranded in the ‘shallows’ of thought.

Carr’s book is a reversal of the usual assumption that up-to-date technology makes its users ‘smarter’ and more sophisticated than people who rely on outdated forms of technology like books or other traditional technologies. But his argument is not free of the deep cultural prejudices that underpin simple oppositions between book culture, orality, and electronic textuality. In particular, by giving book culture the monopoly on ‘deep thinking’ Carr’s work certainly lacks a broader understanding of how communication and thought takes place in ‘continua’ of orality and literacy (Finnegan 1988: 175) as well as through visual communication (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 2008).

m4Lit Example

To illustrate my point, I want to discuss the Shuttleworth Foundation’s m4Lit project. The findings of this research project showed that South African teens use mobile communication technologies as part of a shifting repertoire of modal interactions characterized by interplay between ‘oral’ and ‘literate’ modes of communication, indigenous languages and English, with their mobile phones providing a site for vital cultural creativity.

Like many people around the world, the teens who participated in the study used media technologies in diverse ways to maintain complex social affiliations or interactions, and to develop knowledge of their social network, and to find information through their interpersonal interactions, rather than only through media.

The problems with Carr’s theory of media can be traced back to two venerable scholars, Marshall McLuhan and Walter Ong; both can be described as technological determinists in that they claim that modes of communication determine the ways of thinking and cultural characteristics of entire societies.

The notion that there is a causal relationship between literacy and particular thinking patterns may be an old one, but it is far from universally accepted. One famous study of the effects of literacy on cognition (Scribner and Cole, 1981) set out to prove that literacy had cognitive consequences, only to find that actual interactions between thinking, literacies, and schooling were far more complex than the researchers expected. Science and technology studies depict the mutual interdepence between society and technology (e.g. MacKenzie & Wajcman 1985).

Studies of oral literature even find it hard to define what might be distinctively ‘oral’ or ‘literate’ given the huge diversity of cultural forms and human societies. Instead of looking for ways to generalize this diversity away, scholars of the African oral tradition have called for closer attention to the specific circumstances under which various modes, media and genres of communcation are accessed and produced, and to the social uses of communication (Finnegan, 1988). African scholars have also questioned Ong’s argument about ‘orality’, criticizing its ethnocentric, extravagant and totalizing claims (e.g. Biakolo, 1999).

Carr’s argument in The Shallows does not engage with these critiques, but extends McLuhan’s and Ong’s notions of cognitive consequences to a radical extreme. Carr claims that media use causes changes to the structure of the brain thanks to its ‘neuroplasticity’, or the brain’s ability to form new neural connections and lose old ones. Thus Carr believes that changes to society result when changes in communications media reshape the human brain (Carr, 2010:49).

Mobile Literacies

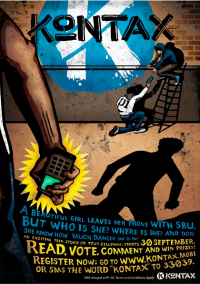

In 2009 I worked on the m4Lit (Mobiles for Literacy) research project with Steve Vosloo (Shuttleworth Foundation) and Ana Deumert (University of Cape Town). We investigated teens’ responses to Kontax, a serialized m-novel for South African teens, which was published on a mobile website and on South African mobile instant messaging platform, MXit (see Walton, 2010 for a more detailed report).

Kontax attracted over 64 000 subscribers in the course of a month-long campaign, a substantial audience when considered in relation to the very small markets for South African publishing. The popularity of the story when released on local mobile instant messaging platform, MXit, showed us conclusively that youth audiences were keen to try out reading fiction on mobile phones.

Kontax was less successful at maintaining readers’ interest and engaging them in immersive reading of the entire series: we estimate that only 7 200 (26%) of Kontax subscribers in the 14-17 age-group were sufficiently engaged by the story to read all 21 chapters.

This was a core group of committed readers, and MXit page-view data suggests that most readers who persevered in reading the third chapter finished the whole story. Nonetheless, almost three quarters of subscribers did not read that far. In fact, most readers abandoned Kontax after reading (or just downloading) only one 400-word episode. This trend may have been even more pronounced for the township teens specifically targeted by the project In interviews, only 10.4% of these teens told the fieldworkers that they had read all the episodes. The rest of the group said that they had planned to read the story, but had not had time to do so, given the many distractions available on MXit and their preference for other forms of literate interaction, such as mobile IM with their friends.

The m4Lit campaign thus appears to have been successful in using the accessibility and novelty of mobile phone fiction to spark interest in Kontax, while it only ‘hooked’ a minority of more committed readers. Our data didn’t allow us to establish whether it was the distractions of the mobile platform (as Carr might argue), the thriller genre, or specific features of the Kontax story that were primarily responsible for this pattern of declining interest.

Carr’s faith in only one mode of literate interaction (lengthy, linear, solitary reading) seems unduly narrow given the rich variety of interactions we observed in the course of the m4Lit project. M4Lit showed that large numbers of teens were eager to try out different modes of engaging with the written word, including reading lengthier texts, correcting errors and typos in the story, writing comments on the unfolding plot, and submitting their own ideas for stories. It also showed how important literate interpersonal interactions through texting and messaging are to their growing knowledge of the world around them, and of themselves.

Teens in fact reported difficulties extricating themselves from highly immersive messaging sessions. Our research showed that their texting and messaging practices centred around peer networking activities. Here the teens valued speed, responsiveness and attentiveness in their mobile conversations. In fact, for them, the marks of orthodox ‘literate’ writing such as punctuation and unabbreviated texts signified ‘newcomers’ who had not yet learned to “write well”, using “MXit language” – a teen ‘hetero-graphy’ (Blommaert, 2008) specifically adapted to this technology, genre of interaction, and social context. As teens grow older and move beyond the context of their local friendship networks these skills are likely to stand them in good stead. Studies of other low income communities around the world show that the ability to use available technology to maintain their relationships, leverage and develop strong social networks are a crucial grassroots survival strategy (e.g. Horst & Miller, 2005, Kolko, Rose and Johnson, 2007, Donner, 2007).

The m4Lit project showed that there could be real drawbacks to using a chatty mobile platform for certain kinds of reading, learning and study. Nonetheless the mobile platform allowed us to reach teens in a way that would have been almost impossible otherwise, and, in the South African context is a highly accessible, relatively cheap option for the growing numbers of people who can access mobile internet (current industry estimates puts this at 9 million South Africans, or about double the number who access the Internet with computers).

At the same time, while exploring all available options for making the most of mobile, we also need to keep up the pressure for government to invest in books, computers, libraries and librarians for schools. I say this not because I share Carr’s cultural prejudices against electronic communication, but because I believe in providing equal access to public education. Mobiles are a private resource which means that students and their parents must shoulder handset costs. They also require ongoing investment in airtime – so inequality of access and participation are built into this educational architecture and are likely to remain its biggest drawback.

Marion Walton is a Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Film and Media Studies at the University of Cape Town, South Africa.

References

Biakolo, Emevwo. (1999) On the Theoretical Foundations of Orality and Literacy. Research in African Literatures 1999 30:2, 42-65.

Blommaert, Jan. 2008. Grassroots Literacy: Writing, identity and voice in Central Africa. Routledge: London.

Donner, J. (2007). The rules of beeping: Exchanging messages via intentional “missed calls‟ on mobile phones. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), article 1. Retrieved Nov 28, 2009, from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol13/issue1/donner.html

Finnegan, Ruth (1988): Literacy and Orality: Studies in the Technology of Communication. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Horst, H. and Miller, D. (2005) From kinship to link-up. Current Anthropology. 46 (5):755-778.

Kress, G.R. and Van Leeuwen, T. Reading Images. 2nd edn. London: Routledge, 2006.

Kolko, B. E., Rose, E. J., and Johnson, E. J. 2007. Communication as information-seeking: the case for mobile social software for developing regions. In Proceedings of the 16th international Conference on World Wide Web (Banff, Alberta, Canada, May 08 – 12, 2007). WWW ’07. ACM, New York, NY, 863-872.

Richard Conyngham and Doron Isaacs. 2010. We can’t afford not to: Costing the provision of functional school libraries in South African public schools. Equal Education

Scribner, Sylvia, and Michael Cole. 1981.The psychology of literacy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walton, Marion. 2010. Mobile literacies & South African teens: Leisure reading, writing, and MXit chatting for teens in Langa and Gugulethu. Research report prepared for the Shuttleworth Foundation’s m4Lit project. http://m4lit.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/m4lit_mobile_literacies_mwalton_20101.pdf

.

The decisive treatise on the future of the book has been written by, who else, Isaac Asimov.

It is called "The Ancient and the Ultimate" (Jan-73, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1973 The Tragedy of the Moon, 1989 Asimov on Science). You can find the first page at: http://www.jstor.org/pss/40009789

Also take a look at the Processed Book Project http://www.prosaix.com/pbos/book-2-2.html

Now having that out of the way. In the whole of history, only a small minority has ever read long texts. The 10% of the M4Lit is large.

This brings us to the basic instincts of humans (yes, instincts, see Steven Pinker "How the mind works" if you do not know how instincts work in humans)

The basic human social behavior (the basic human behavior per se) is to chat. Apes groom, dogs sniff, (some) birds sing, humans chat. For children, this is augmented with extensive play.

Complaining that children play too much games and chat too much is like saying that bird sing too much. It is what they are supposed to do.

A book is a compromise to make one part of chatting long distance: Story telling. The book is a compromise because of technological limitations of the time. Books allow "conversations" over long ranges of time and distance, but only the narrative part of conversations. Newspapers and magazines try to make this long distance conversation it more "chat" like. Blogs, like this one, even go a step further. They make "publishing" really a two way conversation. Texting is the written version of real chat.

Although I love books, they are only an impoverished conversation. And just like not all people like strawberry ice cream or Limburger cheese, not all people will like reading long texts, ie, books.

Everybody can find something on the Internet, especially, a lot of chatting. So people, children, go online in droves to do what they like most, playing and chatting. There was only a minority that liked to read books before the Internet came along. And there will be only a minority that will like it now. But the earlier non-readers were invisible. Now they are very visible.

So the old complaint that people do not read real books, but they read novels, romance, gothic stories, SF, thrillers, magazines, or comics, has morphed into a complaint that children do not read comics anymore, but are chatting on line.

In the previous issue of Nature, there was a Books and Arts article that discussed how computer games were used to teach quite difficult messages (about genetcis, evolution, eg, Spore, and Climate Change).

"Serious fun with computer games" (Nature 466, 695 (5 August 2010) | doi:10.1038/466695a). http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v466/n7307/f…

"Over the past decade, evidence has grown that computer-based play can support learning in schools. Pedagogical studies and evaluations, summarized in a 2006 joint report titled 'Unlimited Learning', by the UK government's education department and a software publishers' association, found that students whose lessons included interactive games were more engaged in curriculum content and demonstrated deeper understanding of concepts than those who did not use games. Better exam scores and teacher ratings resulted when computer games, both commercial and bespoke, were used as support materials."

In my opinion, this is the way to go: Make education relevant and harness the strengths of children. Do not try to force them to regurgitate irrelevant "factoids" learned in ways designed to suit a low-cost teenage day-care center set-up. Instead, make them learn the facts of life and society in ways that ensures they will actually understand them.

I know, I rant too much.

Some truly nice and useful information on this website , as well I think the style has got superb features.