How Student Technology Profiles Effect Open and Distance Learning in South Africa

The University of Pretoria is one of the premier research universities in South Africa, with approximately 40,000 contact students. The University has a comprehensive IT infrastructure and started to introduce the use of online technology officially in the delivery of its contact programmes as early as 1998. The local bandwidth available for the University is currently 10 Gbps, while the international bandwidth is 168 Mbps.

Computer labs were established throughout the University to expand access to computers for students. There are just over 5,000 computers available for students in more than 100 computer labs, and this number is increasing annually. The ratio of computers to students is approximately 6:1.

Infrastructure was put in place, and training courses have been introduced to enable academics to optimise the opportunities that web-based learning can bring and to further enrich the learning environment. Infrastructure was also put in place for lecturers to communicate with their students via SMS technology.

The University also uses Blackboard as its learning management system (LMS). This system was specifically adapted to suit the needs of the University of Pretoria and is called ClickUP. All students receive an e-mail address by default when they enrol at the University, and can access the University’s online environment via their student number, not just on campus, but from wherever they are. All contact students must successfully complete a compulsory semester course in computer literacy in their first year of study.

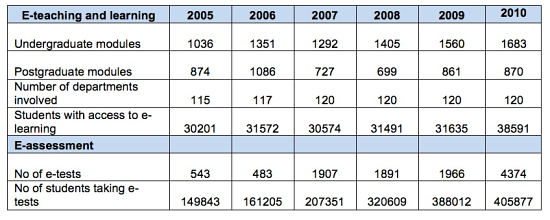

The growth in the number of modules with online (Click UP) support has grown substantially in all faculties/schools since 2005. The total percentage of modules with web support grew from 37.7% in 2005 to more than 75% in 2010.

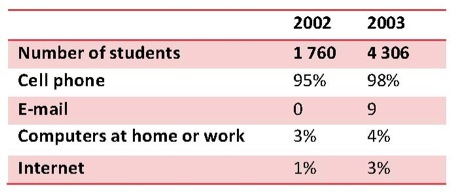

The table below provides an overview of the growth in e-teaching and learning at the University of Pretoria since 2002. In 2009, all academic departments at the University made use of online teaching and learning to a greater or lesser extent.

E-assessment has also developed momentum since 2002. More and more academics started to introduce e-assessment, with the result that more than 380,000 e-tests were conducted in 2009 and 405,877 in 2010.

The profile of the University of Pretoria, as described above, mirrors that of any good university in any developed context. The reason why the University embarked on this e-learning strategy is because the technology is available, affordable, and appropriate to use. Any university that ignores the enrichment that online programmes can bring is irresponsible. It is, however, also true that, universities that embark on IT-enabled learning that cannot be supported by the bandwidth, financial resources, adequate hardware and a target market that can access the technology can be described as irresponsible.

The problem in all developing contexts is that the distribution of ICT is limited to “developed” pockets in these countries. This is also true for South Africa, and is clearly evident in the distance programmes of the University of Pretoria.

In 2002, the Faculty of Education at the University of Pretoria established a Unit for Distance Education to manage the distance education initiative of the Faculty. The Faculty of Education is the only faculty at the University that also presents dedicated distance education programmes over and above the contact programmes. Thousands of teachers (specifically black teachers) were seriously disadvantaged in the apartheid era by inadequate and low-quality teacher training programmes at inferior teacher training colleges established specifically for black teachers.

These teachers teach predominantly in rural areas throughout South Africa. The only way that these teachers can improve their qualifications is through the mode of distance education. In order to play a constructive and significant role in the upgrading of teacher qualifications in South Africa, the Faculty developed distance education programmes in specific subject areas.

In 2002, the University recognised that the student population for distance education differs in many ways from that of contact students. It was therefore decided that the presentation of the distance programmes should predominantly be paper-based, with structured opportunities for face-to-face sessions and other student support services. It was decided that, once students enrolled, an analysis of the student profile would be done to direct the introduction of appropriate ICT to support and enhance learning. The LMS and necessary ICT infrastructure for contact students was available to deliver the distance education programmes online.

Since 2002, just over 39,000 students have enrolled in the distance education programme. Since then, almost 17,000 have graduated. At present, there are approximately 20,000 students in the programme. The distance education students at the University of Pretoria are all teachers with a minimum three-year qualification. Almost 80% of these students are women and more than 85% are older than 35. Just over 50% of the student population are graduate students. The majority, by far, lives and teaches in rural communities throughout South Africa. This profile differs fundamentally from the profile of the University’s contact students.

The technology profile of the distance education students in 2002 and 2003 showed that almost all students had access to or owned a mobile phone. Very few students indicated that they had an e-mail address. Fewer than 5% of the students indicated that they had access to a computer at home or at work. Only 1% indicated that they had access to the Internet.

Profile of students who enrolled for the first time: 2002 to 2003

The above statistics directed the University’s decision about whether or not to introduce the web based/online delivery mode for distance students. This profile also prompted the University to start exploring ways of using mobile phones in its distance programmes. A decision was taken to load all the programme material, with the exception of the textbooks, on the University’s LMS (ClickUP). It was, however, decided that this would not be an interactive site, but only a depository where distance students could access their learning material, as well as the latest tutorial letters and administrative information. Information on the availability of learning material on the website and how to access the site is continuously communicated to existing and new students. Almost no students have ever accessed the site over the years.

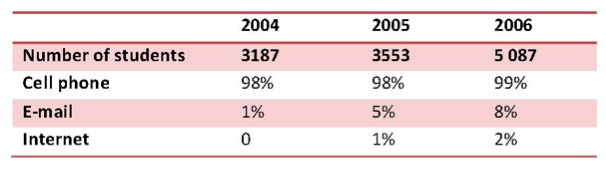

Profile of students who enrolled for the first time: 2004 to 2006

For the period 2004 to 2006, the mobile phone profile stayed the same. The number of students who have an e-mail address remained very low. This is also the case for Internet access.

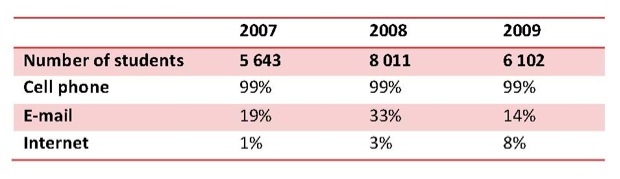

For the period 2007 to 2009, a growth started to be observed in the percentage of students with both e-mail addresses and Internet access. The growth in Internet access rose annually from 2% in 2007 to 7% in 2009, while growth in e-mail use grew from 20% in 2007 to 35% in 2008. However, it declined again in 2009 to less than 20%.

Profile of students who enrolled for the first time: 2007 to 2009

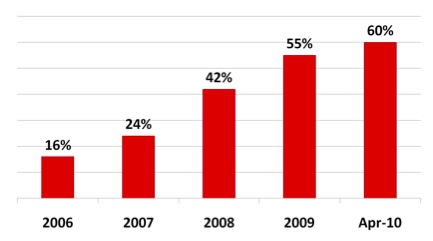

There is, however, a noticeable growth in ownership or availability of computers for distance education students from 2002 to 2010. The figures below give a clear indication of this trend.

The technology profile of the distance education students at the University of Pretoria mirrors the reality of the broader technology profile in South Africa and also in Africa. There are those communities – especially in urban areas – that have comprehensive and adequate ICT connectivity, while the majority of the population living in rural areas have limited or no ICT connectivity.

It was mentioned earlier that, as early as 2003, the University accepted that the technology profile of distance education students differs significantly from that of students on campus and that the delivery of distance education programmes should reflect this reality. It was, therefore, decided that the University should continue to improve the quality of its paper-based learning material and expand and strengthen its student support services within the limitations of the technology profile of the students.

Over the years, the University carefully monitored the technology profile of its students and introduced – in a carefully planned manner – technologies that were accessible, dependable, and affordable to students. This included extensive use of SMSs and, because of the growth in ownership/access to computers, the inclusion of CDs in the learning material. However, because not all students have access to a computer, the information on the CDs is not compulsory content, but information that will enrich their studies, for example, an e-library with recommended readings.

Because a greater number of students have access to computers, more students are typing their assignments and the University has even experienced a rise in the number of students who submit their assignments via e-mail.

The University will continue to monitor the technology profile of its distance education students and introduce appropriate use of technologies to suit this profile. The University foresees a time when the distance education programmes will migrate from being predominantly paper-based to being predominantly delivered online. This is, however, not likely to happen in the near future.

In 2002, a decision was taken to develop a comprehensive and integrated SMS support service for distance students.

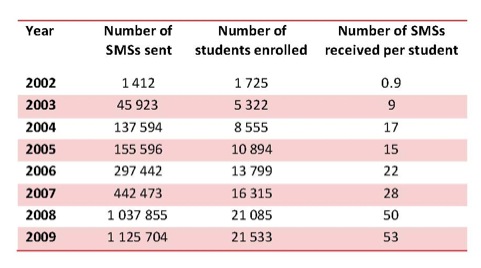

The table below provides an overview of the number of SMSs students receive in the course of a year.

In the first two years, students received a limited number of SMSs. These were mainly to remind them about due dates of assignments. From 2004, the student database was adjusted so that, when a parcel is sent to students, they receive an SMS with the tracking number of the parcel by default. The University also moved away from ad hoc SMSs to a structured SMS communication plan that was carefully designed to enhance and support learning.

It was clear from the start of the study that SMSs could not be used for in-depth academic conversations or to convey complex academic content. It is more about students’ perceptions and how they react when they receive an SMS from the University. In a study among 3,121 students conducted by the Unit for Distance Education (Hendrikz, Viljoen and Adams, 2006), students indicated that they like receiving SMSs from the University. They reported that the SMSs made them feel closer to the University, supported them in structuring their studies, and increased their level of motivation.

The University also embarked on a pilot project to use academic SMSs to support learning. The purpose of this was to try and mimic what a lecturer does in a classroom situation and to translate that into an SMS to support distance students academically.

Conclusion

The Internet and mobile phone penetration rate, as well as South Africa’s ICT development index (IDI), is reflected in the ICT profile of the University of Pretoria as a micro reflection of the reality of South Africa. The University is capable of delivering online distance education programmes, but that would have excluded thousands of students from continuing their studies.

Africa needs to guard against ignorance about the realities of the availability and use of ICT. It must not pretend that it is on par with the developed world and should avoid introducing strategies that are not in line with the realities and context of Africa. Millions of dollars have been wasted on poor ICT decisions in Africa because strategies are not aligned with the realities and context of this continent.

Africa can learn a very important lesson from the experience of the University of Pretoria. One could argue that, if the most advanced sub-Saharan country in Africa reflects this reality in its student population, this student population should be very similar to that of other African countries. We are challenged by the ICT realities in Africa to carefully plan and contextualise our e-learning strategies before introducing them.

In education, it should not be about technology, but rather about how we can expand access to study and how we can improve support to our students in a way that will at least give them a fair opportunity at success.

What an extremely well written and "actionable" article. Congratulations. One question: Do you post the paper-based materials to the students or are they downloadable documents? I am thinking of the cost/distribution problems. Till now, our focus on the African Virtual School has been 100% digital. I wonder, based on your findings, if we should rethink this.

Wilfred Wright

Wilfred

Thank you for your kind comment. We post all our learning material in hard copy to our students. It is possible to download the learning guides but the problem is bandwith and accesibility to the internet in the real rural areas where most of our students live and teach. We are continuesly monitoring the changing technology profile of our students because we know that acces, bandwith as well as affordability is improving rapidly.

Johan

really wow feeling.

nice work pretoria.

our online work is to deliver to every places for everybody with different devices. Text can be printed out in F2F places, internet cafeer and so on. The big issue is that students dont have textbooks in most of cases. in our elearning they have them embedded and can print out if they can or want. USB is one of the tools too.

Thank you, Dr. Hendrikz, for a well researched and presented article.

Towards the end, you say, "It was clear from the start of the study that SMSs could not be used for in-depth academic conversations or to convey complex academic content." This statement was probably formulated in 2002, 9 years ago and SMS is now rapidly becoming outdated technology.

Do you have any other references for your statement? (Or is it simply obvious from the costs that would be incurred in transmitting larger volumes of data via SMS, of so how much data would that be?)

What about newer technologies based on data services, such as MXit, and web/HTML5? Could these transform a relatively cheap mobile phone into a HE learning device?

Dear Johan,

Thanks for a very informative post. It's useful to get some actual figures on student access to technologies.

Given the relatively small number of students who have regular access to the Internet, it makes sense to be cautious about going down the route of online delivery. I’m wondering, though, whether anyone in your unit has looked at the costs and feasibility of delivering course content offline, either through portable media (USB sticks, etc.) or loaded onto a low-cost laptop, netbook, e-book reader or similar device.

In 2008 I did some work in Lesotho on the relative costs of distributing DE materials in paper form (reproduced via digital copying) versus offline delivery. I concluded that it would be cheaper to supply each student with a low-cost device (US$180 or less), pre-loaded with a full set of course materials, than to provide them with paper workbooks for six subjects at senior secondary level. The cost of the device would be recouped through savings on printing costs over the duration of the course (typically 2 to 4 years). If the institution does not want to get into the business of distributing and servicing hardware, it might be possible to make arrangements with commercial suppliers for students to purchase recommended hardware at concessionary rates.

Although the provision of hardware to end users normally accounts for only a fraction of the cost of new e-learning projects, this rule of thumb may not apply under these circumstances. As your institution already produces these materials in digital form, the additional costs of downloading them to individual devices should be minimal.

Once each student has her/his own device, it becomes much easier to introduce a variety of offline and online support services for distance learners.

Yes, that is correct. Online systems do not work well in developing countries.

It should be a combination of both ..online and offline.

We do have such a solution and is deploying now in Nigeria commencing with the teachers and subsequently to the students.

We empower the teachers first using AGE an offline and online system to cover the entire state… even in areas without electricity through the use of solar power/netbook combination.

Alan

Dear Ed

Thank you for the comments – no we have not done a coste analyses of the delivery process you discussed. I am 100% sure that it will be cheaper. As you will know even in developed countries where most people grew up with the internet and computers there is still the practice especially when it comes to learning material that people tend to print the e-material. In our context we will really make it difficult for our students because not all will have the facilities close by to print out the documents if they so wish and they will then also need to pay for that printing. I will be very reluctant to embark on such a stategy given the possible negative impact on learning – the cost of students failing is substantial. We will need to move forward wisely – Johan

I believe that technology will soon render this issue of e-material vs. printing moot. What we need are electronic paper devices of sufficient visual quality and ease of use, with software that allows us to annotate, cross-reference, and search our documents easily.

See the Orson Scott Card short story, The Originist, for an even more advanced design using 3D imaging and intelligent agent software, and an extended example of how it might work. The story was published in Foundation's Friends, a tribute volume to Isaac Asimov.

We start Teacher Training in Rwanda next week. Teachers have broadband, printers and computers. We start with Skype, seeing each others from our countries. Content is develiverd by LMS, we use SMS to give some reminders , short contnet and show how to use mobile tool, too. USB they can use and load down the material. In september we travel to Kihgali to have Action Learning WorkShop. Traffic safety and clean drinking water are the issues to demonstrate how to affect the community and learn. Bolggs and Wiki is used to show the community and give a place like this to comment. The mobiles voice over are used to parents and for reporting back pictures. Its like in Sweden but better !

When you say teacher training, can you elaborate how are they trained? Are they being trained for use of say Skype , getting the contents from LMS or those general things or are they trained in creating contents and delivery them to their students?

If they are creating contents, what authoring tools are they using? Are the contents created online or offline types?

Sure would like to know.

Alan

You can read a number of accounts of teacher training for the use of OLPC XO computers and Sugar Education software in Rwanda online. The Google search

olpc rwanda teacher training

says that it gets 6,500+ hits, starting with this article at OLPC News.

How to Scale OLPC Teacher Training to Reach 43000 Rwandan School … http://www.olpcnews.com/use_cases/…/how_to_scale_teach.... – Cached

7 posts – 3 authors – Last post: Sep 2, 2010

What is OLPC Rwanda's answer to the question of scaling teacher training? Juliano says model OLPC schools: A large part of our work is to …

Dr Johan, do you have any knowledge if the moodle online content delivery systems (open source learning) has been used in South African schools? Since the moodle system is open source, its free, scalable and supported by books, lynda.com video training, as well as having an international community of users who are openly using it throughout the world.I plan to implement it soon at my university in Pakistan http://www.indusvalley.edu.pk