Teacher Training on ICT Cannot Be a One-Time Event

In 2009, I traveled to Macedonia to carry out a monitoring and evaluation study of a nation-wide computers-in-the-schools project that had already been in place for three years. The project was a USAID-funded and AED-led program, Macedonia Connects, originally initiated by request of the president of Macedonia, which provided one computer lab per school.

At the same time, was a public-private-partnership that laid the backbone for competitive broadband wireless Internet service provision to the entire country, by leveraging all primary and secondary schools throughout Macedonia as anchor tenants. That project in itself is a fascinating case, and I have written about it elsewhere

Now I was on-site, three years later, to follow up and see what was happening in the classroom. A major aim of this project was to modernize the Macedonian educational experience so that the children would be able to use technology proficiently, with the goal that eventually Macedonia could become a technology hub for the region.

Teacher Training

The training of the teachers, which was spearheaded by USAID/AED, began prior to the computers arriving in the schools. Training was comprehensive: all primary and secondary-level teachers received training in basic computer use, and then in how to effectively and creatively utilize the technology in their classrooms and pedagogy.

Internationally-recognized experts were brought in to develop and carry out the initial training. All of the trainings aimed to build local capacities by involving teachers as trainers and contributors to the creation of learning materials as well as equipment operators. For many of the trainings, master trainers and teacher trainers were selected from among the teachers by either self-identification or nomination by school directors.

The capacity building also involved advisors from the Ministry of Educational Development as master trainers and active members in the development of materials teams.

During the wave of trainings, a number of progressively advancing skills-development courses were offered, ranging from basic ICT skills classes aimed at enabling teachers with basic technical computer skills, to trainings aimed at integration of the technology into the curriculum.

They were organized over a period of four years, during which time 14,000 teachers from all 360 primary schools and 100 secondary schools received training. The trainings were comprehensive and directed at empowering teachers and school administrations to use technology to improve the teaching process and to enable students to develop the skills and knowledge necessary in a modern society.

We had the impression that the teacher training was state-of-the-art, and of a very high quality. It was additionally impressive for having been carried out on such a large scale, in so short a time-frame.

Data Collection

Data collection and interviews informing this study were carried out from February–December, 2009. The methodology was based on a combination of field methods, such as individual interviews, surveys, and focus group discussions. Quantitative data collection was carried out primarily by a team of 12 local final-year university students or recent graduates with previous experience in carrying out surveys and leading focus group interviews.

The sample was designed as a combination of stratified and convenience sample: all eight regions in the country are represented by two schools (one city and one village school), including schools with both dominantly Macedonian and Albanian language of instruction (represented accordingly). The actual schools were randomly selected from the list of all schools.

Surveys were carried out at each school, while focus group discussions took place in randomly selected schools. In addition, there were individual interviews with the school director or some representative of the administration in each school. All of the surveys, interviews, and focus groups were carried out in the local language, either Macedonian or Albanian, and subsequently translated into English.

Findings

As we published in Technology, Teachers, and Training: Combining Theory with Macedonia’s Experience, in terms of assessing the training they received, three years after the trainings, 51% of the teachers surveyed believed it was sufficient or more than sufficient, while 49% of the total assessed the training as being less than sufficient. A large percentage of teachers expressed the need for further training:

- 95% would like training in specialized educational software;

- 82% in subject specific training;

- 65% in the use of Internet technologies; and

- 37% in basic training for use of ICT.

Also, many teachers expressed uncertainty regarding the use of computers vis-à-vis their students: they consider their students to be far more skilled and knowledgeable then they are and do not want to compromise their authority as teachers by putting themselves into situations where they might encounter a problem that they cannot handle.

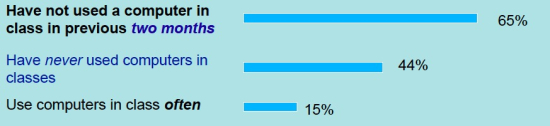

When asked how often they have used computers in class during the previous two months, 65% of teachers responded that they had not used them at all, while an additional 25% had used them only a few times.

Given the statistics above then, it was surprising to us that a rather large percentage (75%) of teachers reported using ICT in their personal lives, either occasionally or very often. A similarly high percentage of teachers reported using ICT in preparing teaching materials and tests (72%), and for lesson-planning (63%).

These could be seen as very positive results, if the goal of the project had been to increase teachers’ use of ICT in their own lives. Yet less than a third of the surveyed teachers use ICT for activities with students, including activities such as: projects (30%); research (34%); working with data (26%); and student assessment (23%). This meant that the goal of actually having the students using the computers in the classroom was far from being realized.

Another remarkable finding for us was that the teachers as a whole were very positive about the idea of ICT in the schools. An overwhelming majority (86%) indicated that they believe that the school is the right place for students to learn basic computer skills.

The Disconnect

What we discovered, therefore, was a marked disconnect between the positive attitude about ICT in the schools and the high level of teachers’ ICT use in everyday life and to prepare lesson plans, and the flip side of the coin, where nearly 60% of the teachers indicated that have never used ICT in their instruction.

This apparent contradiction may be attributable to a number of factors. We believed that one of these factors was an overriding concern, expressed by the teachers themselves during the focus groups discussions, that they lose control over the class when students each have a computer that they can pay attention to instead of the teacher, and that for successful realization of ICT in the instruction, it is necessary that the teacher retains control and knows when to turn off the computer, as one cannot learn solely using the computer. Another factor was the higher degree of technological expertise teachers attribute to their students vis-à-vis themselves, which leads to a feeling of insecurity and loss of authority.

Yet, we felt that this only explained part of the puzzle, since the teachers were using ICT a great deal in their daily lives, and even to plan lessons. Thus, we began to take another look at the training the teachers had received, for clues to help us understand this disconnect. We also looked to theory – one that would take into consideration the teachers’ concerns about adopting technology.

The Theory

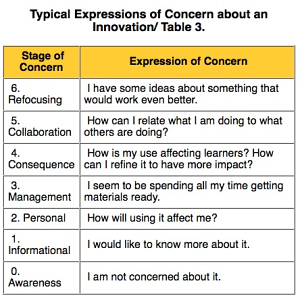

We came upon the Concerns Based Adoption Model (CBAM), which (in a nutshell) argues that change is not a one-time event, and that teachers are the key to educational improvement; their willingness to adopt innovations will determine whether those innovations succeed or fail.

The CBAM model views change as a process experienced by individuals seeking to – or asked to – change their behavior in particular ways. Thus, instead of focusing on improvement of student test scores or other final stage outcomes resulting from a technological intervention – the metric(s) of many policymakers and development and/or aid-organizations – this theory focuses on the process itself and on the individuals crucial to innovation adoption – the teachers.

Several additional points regarding the concept of change underpin the CBAM model: change is accomplished by individuals, and it is a highly personal experience. It involves developmental growth in feelings and skills, and it can be facilitated by interventions directed toward the individuals, innovations, and contexts involved.

CBAM comprises two major dimensions. The first – Stages of Concern (SoC) – describes the feelings and concerns experienced by individuals with regard to an innovation. The second – Levels of Use (LoU) – involves the individuals’ behaviors as they experience the process of change. Both of these are progressive and predictable. Concerns will progress along a continuum as users’ needs and concerns are addressed, to the point where they begin thinking about higher-level concerns (focused on others and impact, instead of on one’s-self), such as the impact of technology on students’ educational experience, from lower-level concerns, such as the fear of how much time it will take them to learn how to use the technology in the first place.

The Levels of Use correspond to and mirror the Stages of Concern – Use of technology will progress to higher-order undertakings, such as working with colleagues to design better ICT-enabled curriculum or even redesigning related software, from lower level usage, which includes basic mastery of how to use the technology.

The bigger point is that concerns and use will not progress unless the concerns evidenced at each stage are effectively addressed, over time, as the individuals/teachers are experiencing them. Since we can predict these stages, we can plan for interventions and trainings that will address the concerns as competence progresses, and concerns and use evolve to higher levels.

This means that the one-and-done format of training, which had been employed in Macedonia, was not going to be effective. We realized that training needed to be ongoing, addressing the teachers’ concerns and needs as they arose, and that they needed support throughout the years-long process of change (which they weren’t getting). Principals and other key school administrators had not expressly received relevant training, and did not understand their key role in supporting the teachers through the change process – and therefore, were not performing this role.

Our recommendations included:

- implementing ongoing training for the next round of technology that will be introduced into the classroom (the government has embarked on a One-Computer-per-Child program, exponentially increasing the number of computers in the schools);

- initiating training that includes the school principals and administration, so that they understand the process of change and their role in supporting this process;

- employing a “technology support teacher” in each school (with the acknowledgement that not all developing world school systems will be able to support this financially),

- making sure that teachers are stakeholders in the technology-in-education process from the beginning, starting with seeking their input on a yearly ICT-in-the-schools plan-of-action promulgated from within each individual school.

Download the full Technology, Teachers, and Training: Combining Theory with Macedonia’s Experience report by Laura Hosman and Maja Cvetanoska

A Few Ruminations

I was only able to carry out this extensive research and survey with the help of Maja Cvetanoska, a local monitoring-and-evaluation expert/practitioner from Macedonia. In other words, as a foreign academic working alone, I never could have carried out this research.

Also, based upon the results we obtained, the M&E specialist (my co-author) was able to work with the educational team to redesign the training that teachers would receive, so that, going forward, it would be revamped and implemented over the long-haul. My colleague also incorporated training for school administrators so that they realized their crucial role over the years-long process of change for the teachers, which was an essential component of the training that had been missing theretofore.

My partnering and working with a practitioner in this case brought about concrete changes as a result of our study and findings. This example underscores the possibility for more widespread effects, as well as positive outcomes, when cross-disciplinary, cross-industry partnerships are formed.

The theory we found, CBAM, had been written in the 1970s and was widely adopted and validated in the academic fields of education and educational psychology since its introduction, but has not, to our knowledge, spread beyond these fields. Yet, because educational projects are frequently the result of policy decisions, and they require the hands-on contributions of people from wide-ranging backgrounds and areas of expertise to be carried out, this framework has much to offer to those from nearly any field studying or implementing technology for development, because the process of change in adopting innovations must be understood and addressed if similar projects are to have a greater chance at succeeding. This is an additional argument for increasing multi-disciplinarity and including expertise from many different areas when working on ICT4D & E projects.

These two points are anecdotal, but are offered up to make the larger case for something I see a great need for in ICT4D or E: working together across disciplines, areas of expertise, and points of view. I am beyond grateful for forums such as this one, where ideas can be shared from experts and interested parties, from across the spectrum of involvement in the subject. When our views are challenged, we are forced to confront them, discard faulty assumptions, or sharpen our arguments and beliefs, etc. This is how we move forward.

Staying in our silos and blindly pursuing a multi-faceted, complex problem from our single point of view or area of expertise is not working. I believe this forum provides a great opportunity to utilize technology to (hopefully) make progress in our ways of thinking about how to better utilize technology.

I’ve been making the case for years that, coming from our various backgrounds and bringing with us our diverse areas of knowledge and expertise, we all have something to offer. As such, the social scientists (like me) need to talk with and work with the engineers and technologists and practitioners and business and industry people and innovators and entrepreneurs.

Because in fact, when we are dealing with trying to harness ICT for Development, we are actually dealing with complex social issues that no single person or area or field can address alone. It’s not easy, but a forum like this one is a great starting point. So, a final word of thanks for the existence of this forum/website and for the spirited viewpoints and contributions of the participants

The recommendations you mention are sensible steps toward incremental change. But disruptive change is pointed to indirectly by the concerns you cite as raised by the teachers in your survey: "…they lose control over the class when students each have a computer that they can pay attention to instead of the teacher, and … for successful realization of ICT in the instruction, it is necessary that the teacher retains control and knows when to turn off the computer…. Another factor was the higher degree of technological expertise teachers attribute to their students vis-à-vis themselves, which leads to a feeling of insecurity and loss of authority." These concerns go to the heart of an important issue. Most teachers have been trained to operate in a teacher-centered, just-in-case learning environment, rather than a student-centered, just-in-time environment. But imagine turning traditional, just-in-case ICT training on its head, beginning with the computer as an opportunity for collaboration, empowering students and learning with them, with teachers exercising authority in the context of respect for student's often-greater expertise as it emerges spontaneously. In this way teachers can model the sense of wonder and passion for learning they hope to inspire in their students. Not everyone can easily make this transition, but ICT training with twin foci on student-centered classrooms and more traditional approaches, each presented respectfully as complementary social experiments, may produce faster results than an incremental approach beginning with traditional methods of instruction. Professional development in ICT that takes place in a teacher-as-learner-centered environment can introduce the student-centered alternative in a way less challenging to the traditional instructional methods teachers employ as teachers.

I look forward to reading the full report. Thank you for your efforts.

Interesting results indeed ! The findings provide valuable insights to perspectives on Teacher training .My research in India based on a ICSSR sponsored project on technology enabled classrooms also revealed similar findings.

The analysis of opinion of teacher educators and survey of teacher eductaion colleges on ICT use highlighted the need to encourage teacher educators to use technology as an instructional resource and to incorporate it while teaching . Refresher courses and in-service courses can make teacher educators aware of new possibilities and new technologies for teaching. The study also generated an ICT integrated teacher education program where ICT components of varying objectives, content and practical skills are incorporated at three phases of Teacher Education program which normally spans one year.

Yes, Technical support is very essential. Teachers tend to use technology and attempt innovations when the going is smooth , hurdles are nil, barriers do not exist and technology is at their finger tips. The study found that teachers were positive about smart classrooms . Schools which had smart classrooms had teachers deploying ICT resources for pedagogy. It was less when those ICT based resources were in computer labs.

With regard to the sense of control , I have observed , teachers are more confident when they are in control. They prefer teacher centered learning environments. I have found smart classrooms to be viable solutions because they retain this element of teacher centeredness. Of the different types of technology enabled classrooms in practice I refer to these as teacher centered technology enabled learning environments.

Dr Ajitha Nayar K,

Innovations in Education and Research Academy,

Trivandrum, India

Dear Laura,

In your article you describe the feeling that ICT4E projects are a failing if they are used everywhere but in the classroom. I exaggerate, but you get the idea.

My problem with this idea is that I do not really see what use the presence of the teacher is when the students are working behind a screen. If a teacher is present, her time can be used more productively when the student pay attention to her teaching. The students could postpone their time behind the keyboard to those moments when the teacher is not present.

You do not present how much time the students spend behind their computers, but if their use is comparable to those of the teachers, I would consider the Macedonian project and complete success.

Cuando me encuentro en clase con mis alumnos (usualmente todas las clases son con computadoras) lo que hago es presentar el plan de trabajo en cinco minutos y los muchachos comienzan a trabajar. Algunos hacen más de la cuenta y con ellos es muy divertido avanzar y descubrir que aprenden más y hacen más cosas de las que hemos solicitado; verificamos su aprendizaje e incrementamos el nivel de dificultad de las tareas asignadas.

Al otro extremo, un grupo de alumnos requiere que uno se siente con ellos, crear un clima de amistad y de confianza para que realicen las tareas.

Mi autoridad en la clase reposa en el cumplimiento estricto de las tareas asignadas y mi conocimiento de cualquier herramienta informática, el dominio que tengo sobre los diversos programas y mi percepción de controlar que esta haciendo cada alumno con la computadora.

Tengo una regla sencilla: puedes hacer todo lo que quieras cuando tenga que calificar, calificare; es tu decisión hacer o no hacer.

Generalmente mis grupos son alumnos entre 15 a 21 años.