High Tech Society Requires a High Touch Childhood

There are plenty of good reasons to be skeptical that ICT can bring about a revolution in education: Lack of solid research showing better learning outcomes than other innovative methods; enormous cost (much of it hidden) in providing sustainable ICT resources and training; and the fact that there is now a long history of educational technology promoters over-promising and under-delivering.

I suspect others in this forum will discuss these issues. But one powerful argument for continuing to inject more technology into schools seems to remain untouched by all of those concerns. That is the inevitability, at least in the foreseeable future that our children’s lives will be saturated with technology and they will have to know how to deal with a technologically driven society. Thus, all academic or financial arguments that might cast doubt on the efficacy of ICT are typically overwhelmed by the sense that we have to adapt education to the realities of the 21st century.

In that respect, it seems to me that the debate over whether schools have to find a place for ICT is over. The only question remaining is how to do it. In this brief introductory comment, I’d like to introduce just one of several factors having to do with the character of ICT that make that “how” question revolutionary in a different way than most technology promoters believe.

Technology Overload

Let me begin by making two general observations: First, adopting any powerful new technology is always a Faustian bargain (Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology). If the 19th and 20th centuries taught us anything about our relationship with technology it should be that. From the internal combustion engine to DDT to antibiotics, there are always some indirect costs or detriments that show up (usually down the line) accompanying the direct benefits that a new technology brings to us. Considering it is children’s lives we are dealing with here, we ought to be much more careful in anticipating and finding ways to minimize those costs than we have been.

Secondly, we need to recognize that the responsibility to prepare young people for a high tech society does not automatically mean that children of all ages should use high tech tools. We don’t prepare children to use alcohol responsibly by teaching them how to drink when they are six. Schools don’t prepare children to deal with sex by surrounding them with sexual activity, or violence by exposing them to violence. Preparing children for social conditions does not necessarily warrant early participation.

Indeed, typically we have seen childhood as a time to prepare for the external challenges of society by strengthening children’s inner resources – self-discipline, emotional control, moral judgment, empathy, etc. – before the opportunities for participation arise.

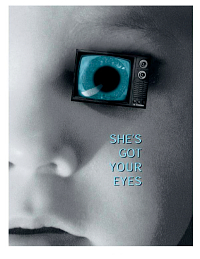

Unfortunately, it is the attention to that entire enterprise of strengthening those inner resources that is likely to be one of the costs of revolutionizing education with ICT. As our moderator has already pointed out, one of the most common arguments for ICT is that it promises “to empower learners.” This is, in large part, because these are extremely powerful tools that we are handing to our children.

We like the idea of our children having all of this power, while hardly acknowledging that handing great power to people who do not bring a strong sense of responsibility to it is a recipe for disaster. Though I do not believe that power necessarily corrupts, it almost certainly does if the bearer of that power has not developed a strong moral and ethical foundation from which to guide its use. Where will that foundation come from in our schools? At what age should we expect our children to possess the maturity to display those moral and ethical qualities?

And to what extent do we actually deny children their most powerful internal learning resources, like quiet contemplation or capacity to endure times of disappointment, by telling them that the answers to their questions are to be found through all of this external power we hand them? Even a child’s greatest learning resource, their curiosity, which tech promoters often claim is set loose by ICT, actually has to be severely restricted for fear of the kinds of information that might get into the wrong hands.

Those pushing for a tech revolution in schools generally ignore these concerns about internal growth, opting instead to “solve” the problem with all kinds of technical fixes, from Acceptable Use Policies to Net Nannies. And in doing so, we simply reinforce the lesson that our children are receiving constantly from every corner of our high tech society: that for every problem there is an external technical solution that does not require the development of one’s inner capacities.

In this respect ICT is just part of an ever deepening problem posed by our relationship with technology: from the five year old who is given a pill because he can’t sit still for an hour, to the adolescent who depends on a spell checker instead of learning to spell, to the high school student who can navigate to mountains of information on the Internet but has not one idea in her head about what to do with it, we are teaching our children every day that solutions to problems lie outside of themselves.

And there is plenty of reason to worry that there are consequences to this trend. For example, self-reporting of college and high school students who plagiarize or in other ways cheat has moved above 70% in the last decade, much of it now enabled by ICT (CaveOn; Common Sense Media). There is much discussion going on across American campuses about the increasing fragility of college students (in the ten years I’ve been teaching at Wittenberg University, for instance, the annual number of students who have sought psychological counseling from the University health office has gone up 600%). And these college students are just the young people our society recognizes as successful.

Time Out from Technology

This is not an attempt to pin all of the responsibility for all of our youth’s troubles on technology. The point I’m trying to make is that further increasing our youth’s already massive engagement with powerful machines is likely to contribute to neglecting the development of the very character traits they need to navigate a high tech society. This fall semester, when I assigned 20 freshman students on the first day of class to spend 15 minutes sitting outside totally away from anyone and without any electronic devices, the initial response by the vast majority was that they had not experienced that level of solitude in years.

To my surprise, they decided to do it every day. When they gave me feedback at the end of the course, they were nearly unanimous in agreeing that the most important thing they had learned in any class this semester was the value of putting their devices away and spending time truly by, and with, themselves.

How sad they were 18 years old before they learned that. How sad that so many young people will never learn that, and that our schools will not even recognize how important an educational resource has been lost. It seems to me that if we really want to prepare our children for dealing with a society saturated with powerful external tools, we ought to be concentrating at the earliest levels on helping them develop their inner resources so that they know the full scope of what we humans are capable of apart from our machines; so they know how to put the power of those machines to good use supporting those capacities; and they know when to put all of those machines away.

In his important book, The Future Does Not Compute, Steve Talbott writes, “What I really fear is the hidden and increasingly powerful machine within us, of which the machines we create are but an expression.” Given that our children now spend over 7 hours a day engaged with media technology (Kaiser Foundation), I think this is a fear those of us in education should take very seriously. After all, it is our job to see that children develop their full capacities, and not become one-sided mechanistic thinkers, no matter how well qualified developing that one side might make them for the job market.

Schools often serve compensatory functions. Marshall McLuhan apparently recognized this when he wrote in his seminal book, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, that schools would have to become “recognized as civil defense against media fallout.” I’m not sure even he could have predicted just how heavy that media fallout would become.

Young people, particularly our youngest, need a time and place where they can take a breather from the constant bombardment of abstract symbols – pictures and texts – flowing from machines; a time and place where they can have direct experiences, sometimes alone, sometimes with caring adults or other children and often with the physical world that they will have no alternative but to live in and take better care of than we have. They need opportunities to learn from all of their senses and all of their inner resources in order to understand where they fit into the world before we give them learning tools whose objective is to give them enormous power over it.

High Tech Requires High Touch

This has been a very sketchy polemic meant not so much to convince as to inspire a different kind of discussion about the proper place for ICT in education. A broader exploration of those views can be found in a couple of my essays – Charlotte’s Webpage and Education Unplugged, respectively – published by Orion magazine, which are available on-line at:

- Charlotte’s Webpage: Why children shouldn’t have the world at their fingertips

- Unplugged Schools: Education can ameliorate, or exacerbate, society’s ills. Which will it be?

I’ll close by saying that there is certainly a place for ICT in education – even a prominent one. I wouldn’t have taught teenagers with and about computers for nearly two decades if I believed that education would not be well served by injecting ICT into the upper levels of schooling.

But there is a serious developmental issue that we have to address with regard to ICT that takes us well beyond the boundaries of the classroom. Just because children can learn from powerful machines doesn’t mean they should. Let’s keep in mind that in making his bargain with the devil, the price Dr. Faustus paid for nearly unlimited power was his soul.

It seems to me that any revolution in education brought on by ICT ought to be formulated to prevent that cost being incurred by our children. As far as I can tell, that means recognizing that preparation for a high tech society requires an intensively high touch childhood.

Thanks so much for this thought-provoking post. (One senses a parent talking)

What I take away is your message that the adults of tomorrow need to be empowered to use tools rather than to be dominated by them. Well yes, of course!! , Children who grow up with technology are quite naturally at home with those technologies in relatively superficial ways: however, it is both the ability to step back from them on the one hand (your example of the "quiet time") and the deep understanding of how they work that need to be developed in school. If one uses the analogy of older, ubiquitous, technologies, schools have never been good at teaching skills in fast-moving fields: from garage mechanics to astronauts, most specific technical skills are better learned through apprenticeship than in classrooms. Classrooms are much better places (when they are good) for helping put in place the learning techniques, encouraging inquisiteveness, requiring rigor, providing a historical perspective and helping young people understand the rewards of effort. Therefore, ICTs in education as elsewhere are a means and not an end.

Finding the right means that ICTs can serve is the major challenge.

There are lots of important points you make here. I'll just concentrate on one that I did not mention in the essay but believe is vital to the conversation. You state that schools should help students develop a deep understanding of how tools work. I agree with this wholeheartedly. The problem is how we go about that task in a developmentally appropriate way. I suggest that eventual comprehension of how computers work – and don't work – is dependent on developing a strong understanding of how physical tools work. Thus, it would be far better to have small children immersed in working with simple tools, gradually introducing and letting them investigate more and more complex tools before they take on these incredibly complex mental tools. Further, I would suggest that the willingness of young people to even pursue a deep understanding of how computer technology works is dependent upon their confidence in understanding how simpler machines operate. Unfortunately, what we are "educating" now is a population of sorcerer's apprentices, who want to wield the power of these machines without any real understanding of how that power works, what it's limitations are or how our minds differ from it. That is dangerous in many ways. The subtly of those dangers is captured beautifully in former MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum's great book, Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation. I encourage anyone interested in this topic to read it.

I think this post does latch well with the ideas in Nick Carr's "The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains". See the ETD discussion at: /archive/literacies-old-a…

I should disclose that I do not believe a single iota of all these fears.

There is a lot of fear-for-the-children in this post. Letting children loose on the Internet would cause serious harm. More or less like letting them running around on the streets blindfolded.

But what are the facts? In the developed world, hundreds of millions of children are online on a daily basis. Just as hundreds of millions of children are walking and biking the streets every day. Do accidents happen?

Yes. Indeed, traffic accidents might be one of the major causes of harm to children. Still, children go outdoors. We also know about the dangers of alcohol with children.

But the Internet? Do our children become seriously harmed in droves by Internet surfing? Where is the evidence?

Just look around, does the Internet cripple 1 in 10 children? 1 in 100? 1 in 10,000? Less?

From everything I have read about this matter, the only working advice is that parents should keep an eye on their children, and inform them about the risks. Just like about the streets.

We do not keep our children indoors all the time until they are 18, why should we keep them off the Internet?

In short, we might look at the Internet as if it was a motorized chain saw or cocaine in a child's hand, but that would be completely irrational. Walking to school is generally much more dangerous than surfing the Internet.

Should I add that posts like this have been written about Novels, Movies, Radio, Comics, and (M)TV?

Meanwhile in Korea…

"English Speaking Robots Become South Korea's Newest Teachers" http://tinyurl.com/3498pzc

Anyway. Reading this post has convinced me that we need something like Godwin's Law http://tinyurl.com/6h49c for arguments on Adopting Tech or New Education Methods, wherefore anyone mentioning Dr. Faust automatically loses.

C'mon Lowell! If at least it were true.. The fact is that we have nothing left to barter. If the Prince of Darkness himself came along, I don't know we could get from him even a NIB copy of Windows Millennium in exchange for whatever little control we still have in the education of our kids or in how technology overwhelms their senses and inputs.

First, Established Education itself has swallowed us, our firstborn, its siblings and has first dibs on their brood for generations to come – that deal was messed up well before we were came along, and Teacher Unions and assorted Government agencies, as well as Publishers and other Dominions and Powers, in effective representation of His Dark Lordship, do pretty much everything they want, including in practice (though they will pretend it ain't so) immersing them in sex, whether to educate them about sex or just because that is part of Hissss plan.

Then, technology itself and big business behind it will cry and cringe in public about kid's misdeeds, all the while making great profits out of those, and pushing for more of that. If you had such bad taste, you could go from a Sony release of music or video to an illegal copy on a Sony-brand CD or DVD without ever touching a screw of another brand – Sony will provide all the tools you ever need to do it, and after charging you prime prices, complain that you used them… Video games advertise as a strong selling point how "addictive" they are. Pretending that a kid (and/or his parents) *can* have the intelligence, skills and strength to resist, especially when humans are so weak when it comes to being themselves in their convictions and resisting peer-pressure, is simply wasting everybody's time and a lot of bytes.

Yet my point is not to dismiss your post. I actually found it quite intriguing and it made me ponder, as lately I have been pursuing a similar line of thought. Definitely our educational models, and society as a whole seem to be losing any chance to help build a moral compass, and whomever is taking up that role has no interest in doing it straight. I agree that technology in itself cannot and won't fix things – and I have published often that such an approach will likely make things worse, notably in those harebrained schemes where the Internet is supposed to step in as the paradigm-changing element, as espoused by OLPC especially in its earlier days "It is no good to give a machine to a child unless they have access to the Internet. Without access, it's just a brick".

So what is left? One, electronics and the Internet and all those titillating alluring calls to mischief or worse are here to stay – kids have no real way out. Disconnect them 15 minutes? cool! Pull the plug for good? not even you could have done it. Two, whatever solution there is will not come from the education establishment, business or those who respond to its lobbies: government and international funding institutions. Which leaves you, me, and a few others, and Acts of God. So, beyond ora et labora, and the call for plain denial of the whole problem (I remember an article somewhere titled "the kids are all right" pretending this media takeover of their brains was nothing we needed be concerned about – nothing to do with the movie of that name, which is what Google gives me when trying to find the source), who knows, maybe fora like this one, and courageous articles like yours, with whatever faults we might like to see in them, while not wanting to sound "air-benderish" I dare say might end up being our last chance. Maybe someone might somehow figure it out, and then that goes viral, and we got Basement Cat foiled again for our time.

It has become fashionable in some circles to discuss how to survive a zombie apocalypse. Of course, in the understanding by all that zombies are not quite real and only in fiction do they go around saying "braaaaains!". Yet sometimes, after debating these matters of quality of education and such, with aprioristic MIT professors or government people in Bolivia, I wonder if we have had those zombies among us already for quite a while, and if so, that the media / IT push is not just a newer way to attune them to a global conscience – and at the same time, for hope's sake, I come across a few people here and there who have managed to not get totally infected. I don't know… But that won't stop me from trying to understand. Thank you for your note!

Meanwhile in Korea…

"English Speaking Robots Become South Korea's Newest Teachers" http://tinyurl.com/3498pzc

Anyway. Reading this post has convinced me that we need something like Godwin's Law http://tinyurl.com/6h49c for arguments on Adopting Tech or New Education Methods, wherefore anyone mentioning Dr. Faust automatically loses.

C'mon Lowell! If at least it were true.. The fact is that we have nothing left to barter. If the Prince of Darkness himself came along, I don't know we could get from him even a NIB copy of Windows Millennium in exchange for whatever little control we still have in the education of our kids or in how technology overwhelms their senses and inputs.

First, Established Education itself has swallowed us, our firstborn, its siblings and has first dibs on their brood for generations to come – that deal was messed up well before we were came along, and Teacher Unions and assorted Government agencies, as well as Publishers and other Dominions and Powers, in effective representation of His Dark Lordship, do pretty much everything they want, including in practice (though they will pretend it ain't so) immersing them in sex, whether to educate them about sex or just because that is part of Hissss plan.

Then, technology itself and big business behind it will cry and cringe in public about kid's misdeeds, all the while making great profits out of those, and pushing for more of that. If you had such bad taste, you could go from a Sony release of music or video to an illegal copy on a Sony-brand CD or DVD without ever touching a screw of another brand – Sony will provide all the tools you ever need to do it, and after charging you prime prices, complain that you used them… Video games advertise as a strong selling point how "addictive" they are. Pretending that a kid (and/or his parents) *can* have the intelligence, skills and strength to resist, especially when humans are so weak when it comes to being themselves in their convictions and resisting peer-pressure, is simply wasting everybody's time and a lot of bytes.

Yet my point is not to dismiss your post. I actually found it quite intriguing and it made me ponder, as lately I have been pursuing a similar line of thought. Definitely our educational models, and society as a whole seem to be losing any chance to help build a moral compass, and whomever is taking up that role has no interest in doing it straight. I agree that technology in itself cannot and won't fix things – and I have published often that such an approach will likely make things worse, notably in those harebrained schemes where the Internet is supposed to step in as the paradigm-changing element, as espoused by OLPC especially in its earlier days "It is no good to give a machine to a child unless they have access to the Internet. Without access, it's just a brick".

So what is left? One, electronics and the Internet and all those titillating alluring calls to mischief or worse are here to stay – kids have no real way out. Disconnect them 15 minutes? cool! Pull the plug for good? not even you could have done it. Two, whatever solution there is will not come from the education establishment, business or those who respond to its lobbies: government and international funding institutions. Which leaves you, me, and a few others, and Acts of God. So, beyond ora et labora, and the call for plain denial of the whole problem (I remember an article somewhere titled "the kids are all right" pretending this media takeover of their brains was nothing we needed be concerned about – nothing to do with the movie of that name, which is what Google gives me when trying to find the source), who knows, maybe fora like this one, and courageous articles like yours, with whatever faults we might like to see in them, while not wanting to sound "air-benderish" I dare say might end up being our last chance. Maybe someone might somehow figure it out, and then that goes viral, and we got Basement Cat foiled again for our time.

It has become fashionable in some circles to discuss how to survive a zombie apocalypse. Of course, in the understanding by all that zombies are not quite real and only in fiction do they go around saying "braaaaains!". Yet sometimes, after debating these matters of quality of education and such, with aprioristic MIT professors or government people in Bolivia, I wonder if we have had those zombies among us already for quite a while, and if so, that the media / IT push is not just a newer way to attune them to a global conscience – and at the same time, for hope's sake, I come across a few people here and there who have managed to not get totally infected. I don't know… But that won't stop me from trying to understand. Thank you for your note!

Yamaplos,

There is more than the US. But all educational systems are conservative. Not all are equaly corrupted by commercial and union considerations.

But one thing is sure. If children want to earn some money later they should prepare to use Ict.

@Yamaplos,

Wow! I must say, you make Ellul look like a cockeyed optimist. But you may be right. I really don't see a strategic way out of this, in part because the problem is so deeply embedded in an ideology that permeates every aspect of our personal, political, community and most emphatically, working lives. Perhaps the best we can hope for is a monastic conservation of the deepest human qualities until this technological ideology finally consumes itself – if it doesn't totally consume us all first (ah, now I'm catching your spirit).

I agree that our educational establishment is complicit in all of this. Its structure serves pretty well the technology god (as Postman referred to it) even as many (a dwindling number, alas) teachers still battle against it. As an teacher myself, I have to believe that we may be able to educate our way out of this. I take some heart from students, who despite getting the shakes after 15 minutes of solitude, seem to be able and willing to criticize the dependency they have fallen into. They aren't a happy generation, and it doesn't take much for them to recognize that their relationship with technology plays a big role in their dissatisfaction. We'll see.

I appreciate your no-holds-bar approach. We need more people raising their voices like that.

Haha! Ellul, never heard of him until now, googled, from what I see in Wikipedia, he and I might have too much in common for comfort: being born in Bolivia, I have tried last year to be active in "thinking globally and acting locally" (turns out that's Ellul's line!) by going there seven months to support the Socialist government in its quest for ICT4E. To say it was a frustrating experience is to be very understated… As an idealist in many ways I am so burned out even months later that I am unsure there is really a way to Better that we can craft – thus Providence in its many ways, and as I posted somewhere recently, random serendipity might count for more than we would actually want to accept as guiding forces. That is where my credentials as a Christian do come handy, as no doubt they did for Ellul. Will have to learn more about him, seems he had a few things IMHO quite straight. Thank you!!!!

I tried to be very careful not to argue that "letting children loose on the Internet would cause serious harm." Reducing my argument to that simplistic charge makes it an easy target to shoot at. What I'm concerned about, and hope we will address in this forum, is what Jacques Ellul characterized as the "convergence of all techniques," including physical technologies, on the integrity of the child as a human being and the impact that has on his/her understanding, values, relationships, competencies with the world all around. I am much less worried about whether a child happens upon some pornography on the Internet, or even gets distracted a lot, as Nick Carr claims, than I am whether she has spent enough time out in nature to understand and appreciate the demands, beauty, pace, etc. of the non-digital world. You say that we don't keep our children indoors until they are 18. Well, at least in the U.S. something is keeping them indoors, and even when they go outdoors the opportunities for engagement with the natural world, or even a quasi natural world, are nearly non-existent for vast numbers of kids (see Richard Louv's Last Child in the Woods). A young child who spends much of his days in the woods and no time on the computer is almost sure to look at the world through a very different lens, both in terms of knowledge and value, than someone who spends the typical 7 hours a day in front of screens and no time in nature. Will a child learn to affiliate with, honor, appreciate and seek ways for humans to live more harmoniously with nature if he grows up in a machine world that promotes the manipulation of and control over one's environment? I think the same concern can be applied to dealing with other human beings.

Of course, what I'm getting at here is a question of value. And I'm not hesitant to admit that I am arguing for a culture that has been losing ground for a long time. If we do not consciously and explicitly compensate for the general cultural dominance of machines and mechanistic thinking in our society, our society, I believe we will all suffer for it. Common sense should tell us that children whose primary relationships early on are with people and nature are far more likely to develop values that support and nurture the health of those relationships than children who almost from the time they can push buttons spend vast amounts of time in primary relationships with machines, no matter how good those machines are at supporting social activities.

Putting this in the context of schools, none of what I've written should be taken as support for "traditional" ways of learning. We turned teaching and learning, at least in this country, into a mechanical operation a century ago. If we continue to insist that teachers and students operate like machines, then by all means, let's get the best machines to do the job. But it seems to me that in a world saturated with technology and mechanical processes, it makes more sense to start out with teaching and learning that really concentrates on developing the fullness of our human capacities, as well as a deep and appreciative understanding of that which is not human made. Where else are children going to get that instruction? From their parents? Sorry, it isn't happening, They are the ones pushing this stuff at their children as soon as they can hold it in their hands.

I would generally agree with you. I must have been reading too fast (at least reaching conclusions too fast).

But when you write

"A young child who spends much of his days in the woods and no time on the computer is almost sure to look at the world through a very different lens, both in terms of knowledge and value, than someone who spends the typical 7 hours a day in front of screens and no time in nature."

I would like to remind you of the fact that half the worlds population (and children) live in (mega-)cities nowadays. That is no less the case in the developing world.

So, half the children in the developing world will experience "nature" to a level that they could do with a lot less outdoor, and some more indoor. And the other half will experience nature only as part of landfills and open ground within shanty towns.

But both groups of children in the developing world do not have a "safe and comfortable" indoors nor have they the option to "run around the woods" as these are either too distant or too dangerous for them (Tom Sawyer in the tropics would stay on the paths or be dead).

Both could do with some more contact with the world outside their village or shanty town, I think.

first time here and just wanted to stop by to say hi there everyone.