OLPC in Paraguay: Will ParaguayEduca’s XO Laptop Deployment Success Scale?

.

In many ways the OLPC project in Paraguay is radically different to Uruguay’s Plan Ceibal which I described in-depth last week and Peru’s Una laptop por niño which I’ll dive into next week.

As already indicated in the introduction of this article series in terms of scale it’s significantly smaller than the efforts in Uruguay and Peru. Whereas these countries have so far distributed 400,000 and 300,000 XOs respectively – and are already in the process of ordering more laptops – Paraguay currently has approximately 4,000 children with XOs. With an additional 5,000 pupils receiving XOs over the coming months the total reach of the project will increase to 9,000 which means that every child enrolled in primary school in the city of Caacupé, the project’s main site, will have received a laptop.

Another major distinction between Paraguay and the other two countries is that an NGO rather than the government is the main driver of the OLPC project. These two different approaches can be found both in the particular context of OLPC as well as ICT for Education projects in general. There’s no doubt that these different starting points often have significant impacts on projects’ approaches, goals, an developments. Some of these differences will be discussed when we explore the six criteria this series is loosely based around later in this article.

In any case, Paraguay’s OLPC project was initiated by ParaguayEduca, an NGO that was started in 2007 out of a group of people’s desire to bring One Laptop per Child to their country. The organization’s main objective is:

“To promote a system of teaching that utilizes ICT as a tool oriented towards collaborative learning which is centered on pupils and integrates the different educational stakeholders found both inside as well as outside the classroom.”

The first step to achieve these goals was the start of a pilot project with 200 XOs in 2008. As mentioned above the program has since been expanded to 4,000 pupils and is scheduled to achieve full saturation in the city it works in over the coming months.

On a personal note it’s worth mentioning that already well before I went to Paraguay I heard a lot about the efforts there and was very intrigued by what seemed to be a very well run project. The reason I heard so much about the project was that during the three months I volunteered with OLE Nepal in Kathmandu in 2009 I shared an apartment with long-term OLPC contributor and volunteer Daniel Drake. Daniel was and is one of the most experienced people when it comes to OLPC implementations given that he has supported in-country teams in many different places around the world: Ethiopia, Nicaragua, Nepal, Nigeria, Peru, Argentina, and of course also Paraguay.

Combined with the information I got from other people who worked in Paraguay and who I met at conferences in Austria and on the U.S. Virgin Islands my expectations were certainly high when I arrived in Paraguay’s capital Asunción in late July 2010.

Just like with my earlier article about Uruguay’s Plan Ceibal I’ll again be using the previously introduced six criteria for successful implementations of ICT for Education projects in developing countries as a guidance for this report.

1. Infrastructure

Similarly to Uruguay’s Plan Ceibal, ParaguayEduca spent a lot of time and resources in the past two years on getting the underlying technical and logistical infrastructure for its project right.

All of the schools which have received XO laptops to date are connected to the country’s electricity grid so there was no need to use alternative power solutions. However the classrooms themselves generally only provide a handful of power outlets so multiple power strips have to be used to enable all the XOs to be charged simultaneously.

When it comes to connectivity ParaguayEduca is cooperating with Personal, one of the largest telecommunications providers in Paraguay, to connect all of the schools where it distributes XOs to the Internet. Since the schools are in or close to the city of Caacupé a wireless WiMAX backbone was installed which connects them to a central 14MBit Internet connection that is shared between all the schools.

On top of that Personal is supporting ParaguayEduca’s efforts by providing this connectivity for free for the first two years after which it’s likely that the schools themselves will have to pay for the connection. Additionally ParaguayEduca has installed a server at every school which so far is mainly used as a storage medium for automated backups of the XOs and as a content repository but could take on additional tasks in the future.

To tie these efforts together and enable monitoring of the network components’ operation, keep track of XOs undergoing repairs and its stock of spare parts as well as other operations related to logistics ParaguayEduca developed its own backend software solution called Inventario which it has released as open-source software. Apart from simplifying as well as facilitating many processes the data the system collects also provides a basis for analysis of factors such as common hardware and software issues or the reliability of different WiFi equipment.

Last but not least ParaguayEduca has also built up significant capabilities when it comes to improving the Sugar software that’s running on OLPC’s XO laptops. Unlike some other OLPC projects the Paraguayan software team has gone beyond just fixing bugs and adapting the software to local requirements. Based on work done by other Sugar developers and partially in collaboration with Uruguayan developers from Plan Ceibal, ParaguayEduca’s team has enhanced Sugar by adding several new features related to accessibility, data backup, 3G connectivity, and system monitoring, releasing them as Sugar 0.88 Dextrose.

There’s no doubt that ParaguayEduca’s team has done an excellent job of establishing the required infrastructure for implementing a successful and potentially large-scale ICT4E project. At the same time it’s great to see them sharing their software and knowledge and collaborating with Uruguay’s Plan Ceibal which enables the wider OLPC community to benefit from their efforts.

2. Maintenance

To address the challenges related to maintenance ParaguayEduca has built up CATS (Centro de Asistencia Técnica y Soporte – Center for Technical Assistance and Support), a small repair team based in Caacupé. As of July 2010 the team consisted of one full-time employee, a half-time employee and several interns.

Currently the repair team visits each of the 10 schools which have received laptops so far on a weekly basis. Laptops with minor issues are repaired on the spot while the remaining ones are taken back to the repair team’s office. Before any repairs are undertaken a laptop’s issues are entered into the Inventario system mentioned earlier which enables both ParaguayEduca’s team in Asunción as well as the CATS team itself to accurately track which kind of issues are regularly encountered in the field.

Not surprisingly the issues encountered in Paraguay are relatively similar to the ones being observed in Uruguay. Software and problems with the activation system are the most common issues that the repair team has to deal with. In terms of the hardware broken chargers, displays, and keyboards are at the top of Inventario’s “failure by cause” chart.

When it comes to the hardware failures efforts are currently underway at OLPC to redesign the chargers that XOs are shipped with in order to address the issues encountered with them. Similarly the next batch of 5,000 XOs should have significantly less keyboard issues due to the fact that upon receiving reports from Uruguay of them regularly being broken OLPC increased the thickness of the keyboard’s membrane to make it more robust

One important difference is that unlike in Uruguay where a warranty covers some types of breakages in Paraguay spare parts needed for repairs currently have to be paid for by the pupils’ parents who often can’t afford the cost. In combination with difficulties PraguayEduca encountered when purchasing spare parts this has led to a number of cases where broken XOs simply haven’t been repaired. Obviously this is less of an issue with chargers which can be borrowed from other people but leads to an unusable laptop when the display is concerned. As a result an estimated 20% of the pupils are currently without a working XO which results in laptop-based classroom activities being more difficult for teachers.

Overall maintenance is proving to be an area which creates significant challenges for the OLPC deployment in Paraguay. The current approach with having the repair team based in the same city where the pilot project is taking place definitely has a lot of advantages. The regular visits by the repair team combined with the intensive in-classroom support provided by ParaguayEduca (more on that under “teacher training”) significantly lowers the barrier to entry to the maintenance and repair process. This results in basically all breakages being reported and subsequently addressed within a week which is a stark contrast to Uruguay where up to two thirds of XO breakages seem to be going unreported.

Now the question is just how scalable the current process will turn out to be once the next 5,000 XOs are delivered. Given that some of the schools involved in that upcoming stage are further away from Caacupé it will be interesting to see whether the repair team’s weekly-visit schedule can be kept going or if the frequency of these visits will decrease. Similarly ParaguayEduca needs to find ways to ensure the availability of a steady stock of spare parts to enable the repair team to repair hardware breakages. Last but not least the organization needs to come up with ways to allow children of families who can’t afford expensive spare parts to still be able to use fully functioning XO laptops in class. Whether this can be best achieved via subsidized repairs, external sponsoring for spare parts, making short-term loans of XOs available or a different measure remains to be seen.

Similarly to my thoughts about maintenance in Uruguay I believe that the issues described above can and will be adequately addressed by ParaguayEduca over the coming months. However it again shows that even with seemingly robust devices such as the XO laptop maintenance must be a key consideration for any ICT4E project.

3. Contents and materials

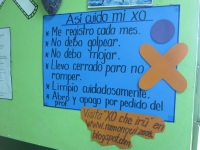

Given its strong focus on constructionist learning ParaguayEduca education team is working hard on developing ways in which teachers can effectively leverage the various Activities and capabilities of the XO and the Sugar software platform. Therefore the educational content they provide teachers with is guidance on how to use the laptops within the school context rather than developing new digital learning objects such as games or other interactive media.

A lot of the education efforts revolve around the use of Scratch, a powerful and versatile programming environment specifically developed for use in education. Examples of the use of Scratch in Caacupé range from simple animations over interactive story-books to extensive games with multiple levels and the integration of environmental sensors. Extensive support for this approach has been given to ParguayEduca by Claudia Urrea who works for OLPC’s education team.

Additionally teachers are also encouraged to use the photo capabilities of the XO as well as other standard Activities such as the Web browser or text processor. This has resulted in a broad range of interesting projects developed by individual teachers. One that I particularly liked was based around homework where pupils were asked to take a photo of a tree at home or on their way to school. The resulting photos were then compared and the trees individual parts subsequently labeled by the pupils.

In the future I also expect to see more use of Sugar Turtle Blocks Activity (which is similar to Logo) given that Walter Bender of Sugar Labs and OLPC led a workshops about its use in Paraguay in June which sparked the education team’s interest. Similarly the education team also expressed an interest in learning more about eToys, another powerful media authoring and programming tool.

Similar to Plan Ceibal and other OLPC projects ParaguayEduca has also established an online library where it shares content and materials ranging from handbooks on how to use certain Activities over works of literature to a broad selection of audio, images, and videos. Given that all the project schools have Internet access this portal is a valuable resource to both teachers and pupils.

Additionally teachers in Caacupé are also encouraged to look at and use materials created by the OLPC projects in Peru and Uruguay therefore enabling them to benefit and be inspired from work done by fellow teachers in these countries.

Overall ParaguayEduca’s educational approach is closely aligned with constructionism that OLPC and Sugar Labs are also very strongly associated with. The education team in Asunción has followed this approach all the way through and built up some great capabilities and knowledge about the use of tools like Scratch in education. Combined with what is apparently a relatively constructionist national curriculum this approach and its strong teacher support component (see the “teacher training” section for further information) has a good chance of having a solid impact on how pupils in Caacupé are being taught with the XOs.

4. Community inclusion

Given its history of being started by a small group of engaged individuals it shouldn’t come as a surprise that ParaguayEduca has been working closely with a variety of different groups and communities in Caacupé to ensure broad support for its project. In many ways, particularly when it comes to local administrators, this process has been facilitated by the fact that Caacupé has been the site of a variety of innovative educational programs in the past which results in people being more open and accustomed to new things being tried out in schools.

Thanks to its formadores (see the “teacher training” section for more information), the repair team, and frequent visits by staff from Asunción ParaguayEduca has managed to establish a strong and continued presence in the local community and the education system. Recruiting people from Caacupé who are part of the community rather than relying on outsiders has been a key component in creating a high level of trust between the various stakeholders and the organization.

One example of the resulting collaboration between ParaguayEduca and other local organizations was a joint event that took place during Día Del Niño (Children’s Day). At the event ParaguayEduca wanted to demonstrate its project as well as highlight some of things that pupils and teachers had created on their XOs. So in preparation for Día Del Niño it organized meetings with other organizations to coordinate several activities such as a booth on Caacupé’s main square. It’s thanks to this kind of approach that ParaguayEduca generally seems to be considered a part of the local community rather than an outsider trying to force its own agenda on the schools.

Apart from this type of work in Caacupé, ParaguayEduca has also been working with the computer science faculty at Paraguay’s largest university, Universidad Nacional de Asunción, to teach students how to get involved in contributing to its project. Its efforts in that area range from offering internships – which are also open to students from other countries – to courses for teaching the basics of programming for the XO.

To sum up it’s safe to say that ParaguayEduca has done a great job in reaching out to various stakeholders within the context of its pilot project in Caacupé and that this will prove to be a solid foundation for continued collaboration in the future.

5. Teacher training

One area where ParaguayEduca’s efforts are a class of their own is teacher training which in other projects unfortunately often doesn’t seem to receive the attention it deserves.

An interesting aspect here is that ParaguayEduca’s education team doesn’t train the teachers directly anymore like it did early on. Rather at the end of 2009 the organization decided to hire people who had previously worked as teachers or trainers themselves and in turn trained them to become “formadores” (teacher trainers). These formadores – currently ParaguayEduca employs 15 of them – are subsequently in charge of the training sessions for teachers before XOs are distributed in their respective schools.

While I was in Paraguay a large number of teachers received training sessions in anticipation for the arrival of the next 5,000 XO laptops and so I had a chance to observe some sessions myself. The teacher training always takes place during vacations when Paraguayan teachers generally seem to be expected to attend courses for their continued education. It’s also the only suitable timeframe to accommodate the 150 hours of training sessions that the teachers participate in.

Just to give you a reference: the most extensive teacher training at any OLPC project that I had been aware of before is provided by Open Learning Exchange Nepal and consists of roughly 80 hours of training over 10 days. In other countries teacher training generally seems to hover around the 40 hours mark.

Of course the effectiveness of teacher training doesn’t just depend on its quantity but also its quality. While it’s impossible to thoroughly assess quality from a few short observations the impression I got was definitely a very favorable one. The training sessions I attended generally focused on how to use the laptop for learning related activities, rather than learning how to use a particular program. Too often the opposite is the case which tends to result in teachers not knowing how to integrate new devices into the classroom routine.

To complement this training the formadores also spend a significant amount of time supporting the teachers in-class once the XOs have been distributed in the schools. The focus there is to help with the integration of the XOs in the teaching process. Additionally it’s no secret that having a helping hand in the classroom makes a lot of difference and facilitates the teaching process.

One simple example is when a pupil runs into an issue – be it a program not starting or the mouse not behaving as expected – a single teacher can normally either interrupt the class to attend to that one pupil or continue the class which results in that pupil falling behind and not being able to participate. In such a scenario a formador being present in the classroom can simply help individual pupils having issues while the teacher continues the normal class.

So overall it’s easy to see that I was thoroughly impressed by the teacher training and support that ParaguayEduca has established. These teacher-centric efforts have really been at the heart of the organization’s work rather than an after-thought as it’s often the case.

Going forward it will be interesting to see how ParaguayEduca can scale the approach to teacher training to potentially include the whole country. In that area the project can definitely benefit from some of the Uruguayan experiences in this context.

6. Evaluation

This is an area which turned out to be significantly harder to investigate than I had anticipated. Before arriving in Asunción I had heard about an evaluation by the Inter-American Development Bank which had also contributed some funding to the first phase of the project in Caacupé. I now found out that this evaluation is still ongoing hence no reports or results are available just yet.

Similarly the Paraguayan alda foundation was involved in early monitoring and evaluation work in 2008 yet again I wasn’t able to obtain a copy of any resulting reports.

A third and still ongoing effort in this area is a PhD thesis by Morgan Ames from Stanford’s Department of Communication. Her work is focused on exploring the educational and social impacts of the OLPC projects in Paraguay and Uruguay on pupils, parents, and teachers. To that end she has conducted more than 130 interviews to date and once completed her thesis is almost bound to become a must-read for people working within the OLPC and larger ICT4E context.

Last but not least and more on a monitoring rather than evaluation level there are also efforts under way to gather data about the usage of the Activities that are available for the XO laptops. This is meant to be a first step to address questions such as which Activities are popular, which ones are used inside and outside school, whether there are differences between how boys and girls use the laptops, etc.

To sum up: There are a variety of evaluations which have taken or are taking place within the context of ParaguayEduca’s project. However the fact that the results of these evaluations don’t seem to be readily accessible – unless I totally missed something – is quite a major let-down in my opinion.

Having said that I feel it is worth mentioning that given its limited resources it’s partially understandable that ParaguayEduca has focused the majority of its energy on building up what I believe to be a solid foundation and infrastructure for its project. Yet it seems necessary for in-depth evaluations to receive significantly more attention in the future, particularly since ParaguayEduca hopes to expand the OLPC project beyond Caacupé which will likely require solid evidence about its impact.

Summary and Outlook

The OLPC project led by ParaguayEduca is without a doubt a very impressive and effective operation. The organization’s focus on getting the infrastructure right in combination with their extensive teacher training and support as well as their knowledge about the effective use of the XOs in the broader learning context makes for a very strong project. In all of these areas other organizations and projects – regardless of whether they’re using OLPC XOs or other devices – can definitely learn a lot from ParaguayEduca’s experiences. Hence it’s great to see them already collaborating and sharing with Uruguay’s Plan Ceibal and the larger OLPC and Sugar communities.

The core question over the next year or two will now be whether the current approaches, processes, and structures can be made to scale efficiently. The upcoming increase from the current 4,000 to a total of 9,000 XOs will likely require some changes in how ParaguayEduca works in areas such as maintenance, ensuring consistent quality of teacher training, and ensuring the long-term sustainability of aspects such as the Internet access. So the organizational challenge will be how to turn what is a relatively small effective project into one that is also efficient on a larger, potentially nation-wide, scale.

Given ParaguayEduca’s track record and status quo I’m convinced that it is in a very good position to run and expand its successful OLPC project over the coming years. Other OLPC and ICT4E initiatives should definitely watch this one closely over the coming months and years!

OLPC in Paraguay is part of an overview of OLPC in South America, a first-hand report of XO laptop deployments in Uruguay, Paraguay, and Peru by Christoph Derndorfer.

Hi… Christoph Derndorfer

World Bank Conceptual framework 2006

At 2005, infoDev establishing an International development agencies, coordinated by the secretary of the Department's Global Information Technology and Communications of the World Bank.

InfoDev is working with different donor countries to provide access to information, enhance development and reduce poverty having as main tools the intensive use of information technology and communications.

In the same year published InfoDev Monitoring and Evaluation of ICT in Education Projects, A handbook for Developing Countries. In this document we can see a conceptual model that identifies the variables that come into play when deciding to adopt information technologies and communications in education systems. It is noteworthy that this model aims to increase students' skills through the use of these tools and point all the other variables in the attainment of this task.

Importantly, this model as the former has in mind the participation of teachers which means allocating financial and logistic resources for training and training in the use of information technology and communication within the school. This aspect is critical in any project of adopting information technologies for one simple reason: the educational system in the world, still rely on teachers to teach students and not conceived a school without teachers. For this simple reason the model, and any other model, should consider the variable of teacher training being this very complex to solve.

Sources 2006 World Bank Conceptual Framework

Wagner, Daniel A., Bob Day, Tina James, Robert B. Kozma, Jonathan Miller and Tim Unwin. 2005. Monitoring

and Evaluation of ICT in Education Projects: A Handbook for Developing Countries. Washington, DC: infoDev /

World Bank. Available at: http://www.infodev.org/en/Publication.9.html

Inter-American Development Bank 2009

The Inter-American Development Bank published a document entitled Projects for the use of Information and Communication Technologies in Education, Conceptual Framework by Eugene C. Severin, this year.

This paper presents a conceptual model for the adoption of information technologies and communications in education. Like the previous model, the emphasis is aimed at students increase their levels of learning. The way resources are organized to accomplish this task is different.

The pattern is clear in its approach. Viewed as a set of inputs, outputs and impact processes and allows us to observe a set of variables that must be taken into account in managing the integration of information technologies and communications in education systems.

In this model, there is a section called: development phase. This section coincides with the matrix of Morel which was designed in 2001 by the UNESCO Institute of Information Technology in Education. Adopting this matrix is possible to consider a progressive measure the progress of the incorporation of information technologies and communications in terms of inputs, outputs and processes and impacts, which vary according to the level where the project is under Morel matrix.

Source 2009 Inter american Development Bank

Inter-American Development Bank (2010), Projects for the use of Information and Communication Technologies in Education. A conceptual framework. Eugenio Severin C. http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?d…

UNESCO. (2003a). Consultative Workshop on Performance Indicators for ICT in Education. Bangkok: UNESCO Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education .http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ict/ebooks/ICTindicators/ICTindicators.pdf

I think that you must to cite more sources about that framework you purpose. Other issue is to think in two levels of actions: national and local. I notices that both are united in your analysis and this must to divide.

Manuel,The conceptual frameworks you reference apply to the impact of ICT on the educational performance of students. That's not what Christoph is trying to measure with his six criteria for successful implementations of ICT for Education projects in developing countries. Christoph is looking at the deployment of ICT in educational systems at the technology project level – how successful was the deployment of ICT and what lessons others can learn from it.While not as robust as the frameworks you mention, his approach makes sense when you look at it from an ICT project implementer perspective. In fact, I've already adopted the framework to improve the ICT deployments I develop and implement.

….I just wanted to share with the community in general the news about the evaluations in Paraguay. Fundacion Alda funded by IDB has finished its evaluation, Instituto Superior de Educacon (ISE) funded by CONACYT has also finished its evaluation. At PYEduca we are starting to develop the instrument to evaluate Reading Comprehension and Logical

and Mathematical Thinking to the kids receiving their XOs in February. You are right rigid and well conducted evaluations are a "must". Pacita Peña

PYEduca