Key to ICT4E Sustainability: Cost-Benefit Analysis

Sustainability is generally associated with ecological systems. Fortunately for us, the educational system is not nearly as complex as natural ecological systems. In the latter, numerous subsystems, linked in a complex relationship of interdependencies and feedback loops, interact non-linearly and are hard to comprehend. The delicately balanced dynamic equilibrium of complex ecosystems can be perturbed by human actions, sometimes leading to dire unintended consequences. The notion of sustainability of complex ecosystems is hard enough to define, leave alone figuring out how to maintain them through time.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

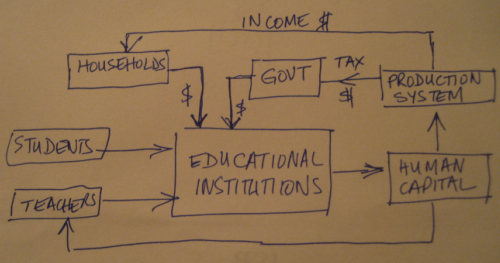

The educational system is a much simpler beast in comparison. A schematic showing the major subsystems can be drawn on a paper napkin over a cup of coffee.

.

Sustainability of the system itself is a matter of getting sufficient funding to keep the accounting books straight. One needs nothing fancier than that well-worn classical tool – cost-benefit analysis – to figure out whether an intended action would make the system better or make it worse.

The tool is simple enough but care has to be taken in its use. The full cost – which means the opportunity cost – has to be considered and weighed against the benefits, for an appropriately chosen period. Sustainability in the present context of the use ICT in education would mean that over some pre-defined period, the benefits at the very least justify the costs. That leaves only the problem of how to measure the relevant benefits and costs.

Also it must be acknowledged that there is no such thing as “the educational system.” There are numerous educational systems, each with its own constraints as defined by various socio-economic conditions. Whether a specific intervention is sustainable or not depends on the type of educational system. More concretely, the introduction of high technology could be sustainable in high-income countries but not in low-income countries. Or the introduction of high technology could be sustainable where human capital (teachers) is relatively more expensive than technology, not otherwise.

ICT has the advantage of scale economies, a feature that is almost entirely missing in human labor-intensive teaching methods. Scale economies means that the average cost drops as the quantities supplied increases. They arise wherever fixed costs are high but the marginal cost of supplying is very low. ICT solutions will be particularly effective – and therefore that much more sustainable – in places where the numbers are large.

Fortunately, large numbers are easily encountered in many environments. Furthermore, these large numbers need not be geographically concentrated. Advances in communications (the “C” in ICT) technologies have made it extremely cheap to record, store, transmit, and remotely retrieve information over long distances. Moreover, content is a non-rival good. It means that one person’s use of the good does not diminish the quantity available for others. Together, those two facts imply that educational content once created can be used by many who are geographically dispersed. This argues for the use of widespread use of ICT and points to its sustainability.

Costs and Benefits are Relative

Another point worth keeping in mind is that there are various levels of education, from primary education to extremely highly specialized education at the tertiary level. While in most cases, education at the higher end of the spectrum must involve ICT, whether ICT can be sustainably used at the lower end of the spectrum is a matter that is context sensitive.

For example, in Berkeley, California, technology is cheap relative to labor. There it makes sense to use computers to address adult illiteracy (to the extent that there is adult illiteracy.) In the numerous public libraries in Berkeley, computers are available by the scores and anyone who wishes can use them for free. The wages of a tutor, however, are very high.

Compare the Berkeley situation with say a small town, Akola, in the Indian state of Maharashtra. Akola does not have freely available computers in public libraries. Actually, there are no public libraries in Akola. The cost of deploying, maintaining and using one computer – which could be used by at most a hand-full of people – would be comparable to the annual per capita income of India. Instead, employing a person to teach adult literacy using the same money would benefit dozens of learners.

I argue that one has to be careful about figuring in the full cost of an intervention. This becomes especially important when subsidies are introduced which distort the true costs. Subsidies for computers may make it appear as if the cost-benefit calculus is working out but in truth it could be that a more comprehensive calculation would reveal that the costs exceed the benefits. Resources of all kinds have alternative uses and what is spent on subsidies in one area is not available for spending on other areas.

This topic of what sustainability means in the context of the use of ICT in education is fascinating and important. It’s rich with possibilities and focusing attention on it can have definite policy implications. The welfare impacts of a good ICT use policy are far from trivial and therefore the topic deserves our serious attention.

Hmm… I think that using a "simple" cost-benefit analysis greatly oversimplifies sustainability measurements. Let's just take two parts of the whole:

On Costs:

You mention ICT subsidies as a distortion of true costs, but there are infinite numbers of subsidies for educational inputs, from reduced taxes on inputs to discounts for teachers outside of school. I think you have to account for them, but also accept them as part of the cost analysis – not exclude ICT-specific ones.

At the same time, your model has a major cost flaw – the price inelastic nature of education in the eyes of a parent. No matter the cost, most parents will just work harder if school fees go up – as long as the parents perceive a benefit to the child. Which brings us to…

On Benefits:

I think we still have a very inexact method of measuring benefits of educational inputs. Standardized tests only measure how well students can take tests designed for some mythical average student. Per-student evaluations are too time-consuming on a large scale. So we're left with "a feeling" that something is benefiting (or not) the student.

And again, if a parent perceives there to be a benefit, they will disregard (most) costs in their assessment, making a rational, objective cost-benefit analysis moot. Parents as voters, will make the educational system spend more on that benefit, no matter the cost.

Wayan:

I agree that ICT is not the only input to education which is sometimes subsidized. But that fact alone cannot be used to disregard the cost-benefit analysis of ICT in education for figuring out whether ICT is sustainable.

Generally speaking, subsidies are justified under specific circumstances. For instance, in the supply of public goods, where there are positive externalities, the market will under-provide. In those cases, subsidizing the costs will align the output to the socially optimal level.

Should ICT use in schools be subsidized? Maybe, if a case can be made that it is a public good and there is a possibility of a market failure. But even then, one can use cost-benefit analysis: only in this case the comparison is between social costs and social benefits (where "social" include the private and the external.)

Atanu

On Costs:

Just because market-distorting policies can take a wide variety of forms doesn't preclude rolling them up into a single input to the system. The cost distortions resulting have a limited number of effects so for purposes of identifying their effect on the success of the overall policy there isn't any need to over-analyze.

Also, Wayan, you've got to read some of Dr. James Tooley's work if you believe in the inelastic price nature of education.

Heck, you don't even have to leave the U.S. to appreciate that education is most certainly price-elastic. Part of housing prices in the U.S. is a function of the perceived quality of the local public education establishment and in the poorer parts of the world parents pay out of pocket for private education at what in the U.S. would hardly be considered pocket change when there is, theoretically, tax-supported public education available.

Your claim of price inelasticity in education comes from the perception that no amount of other people's money is too much to spend on your own child. But where mommies and daddies have to spend their own money they do a careful job of comparing what the school offers to what they have to spend.

Heck, the price elasticity of education is evident at the national level. Nations spend both absolute and per capita percentages on education based on the perception of the value of education.

What you, and most others as far as I can determine, are missing is that price elasticity at the national level has an entirely different meaning then it does at the level of the individual family.

At any level other then the family price elasticity is a function of political power and not of educational quality.

A nation, or a school district, doesn't spend more money to get a better education for its next generation but as a measure of the political influence of those who are dependent upon and who benefit from the education system – teachers, administrators, suppliers, etc. But not kids since the benefit to them won't be available for use for a decade or two and it isn't parents because, to a very great degree, parental opinion is unimportant where education is a public institution.

On benefits:

Where it's difficult to measure what you are interested in measuring you look for proxies.

Poor parents who send their kids to their poor private schools look at their children's enthusiasm, the way the school operator treats the children and the parents and any other measure that may be, if not objective and quantifiable, satisfies the person parting with their few rupees per month. Their decision is aggregated in the survival of the school.

But in the wealthier nations those informal measure are supplemented by more formal means of determining efficacy. ACTs are still an important component of acceptance to higher education and if they are less then perfect what isn't? But those standardized tests are good enough for the purposes of the colleges. They help colleges weed out unprepared and unqualified candidates and if they sometimes miss tomorrow's Nobel Prize winner, well, it's a volume business and you give up precision for utility.

The same trade-off works at the lower educational level. Every test doesn't have to encompass all the glorious diversity of the human spirit if all you want to know is whether a school teaches most kids to read reasonably well in a reasonable amount of time.

So testing is most assuredly doable, it's most assuredly good enough for practical purposes where the need is sufficient like entry to higher education.

Colleges do testing not just because there are a limited number of freshman slots but because within a couple of years those freshman are going to be doing the grunt-work of upholding the reputation of the school. When the big-name professor needs skilled, educated but cheap manpower that professor looks to the grad students and they'd better measure up. You can't do the sorts of research necessary to put your school on the map with grad students who aren't smart enough. In order to make sure your grad students measure up you make sure your freshman class measures up and you do that via test scores.

If you can construct tests to determine if an eighteen year-old is sufficiently prepared and sufficiently smart to have a good chance of doing well in college they you can construct tests that determine whether a school's doing a good job of teaching kids to read and write and add. The difference between the two is that the reputations of colleges rise and fall on the basis of the graduates they send into the world and the reputation of K-12 schools is, to a great extent, unconnected to the graduates, or lack thereof, that they send into the world.

Allen:

I totally agree with you on "At any level other then the family price elasticity is a function of political power and not of educational quality."

For government officials and bureaucrats, the quantity they buy of education (or anything else for that matter) with other people's money is certainly very price inelastic. And that is the source of my major fear. The educational system in India is heavily controlled by the government. Bureaucrats and politicians are in control. Their stated goal is to improve the education system and only those solutions appeal to them that require more spending of other people's money and greater political control.

Atanu

Powerful blog entry. You definitely know what you are talking about here. Im so glad I was able to find your site. I look to see more awesome writing from you. Keep up the excellent work