We Cannot Train More Teachers, We Must Empower Them with Technology

.

The most popular answer to the question of how to improve the quality of schools and education in developing countries is: Invest in more teachers and more schools.

Let there be more teachers

I think there are few people who would contest that having one full time, fully qualified teacher in front of every class of 25 children would bring education of the highest standards to any country.

But could this really be the solution to the educational problems in poor countries? I sincerely doubt whether this solution is feasible. I even fear it is completely impossible to solve the plight of education in the developing world by this route alone.

Here is a statistic that paints a bleak picture, indeed:

India has one of the lowest ratio of teachers. In the US, it’s 3,200 teachers per million people, in the Caribbean it’s 1,500, in the Arab countries it’s 800 and in India it’s 456 teachers per million people. The Times of India (2009)

The US might not be the best example, but even to get at the level of the Caribbean, the Arab countries must double their number of teachers, and India must more than triple its number. And that would be just the number of teachers needed to get at the level of the Caribbean. If the teacher pupil ratio should get close to that of the US, double the number of new teachers would be needed.

Obviously, if the aim would be to decrease the number of pupils per teacher in all developing countries to the level of the developed countries, enormous numbers of teacher would have to be recruited and trained. For many countries in the developing world the number of teachers would have to double, like in the Arab world, in others it would have to triple, like in India and many African countries.

A lot of numbers

How many teachers would have to be recruited, trained, and send to schools? Below, a lot of statistics will be presented. If you are already convinced, you can skip the arithmetic and go to the next section.

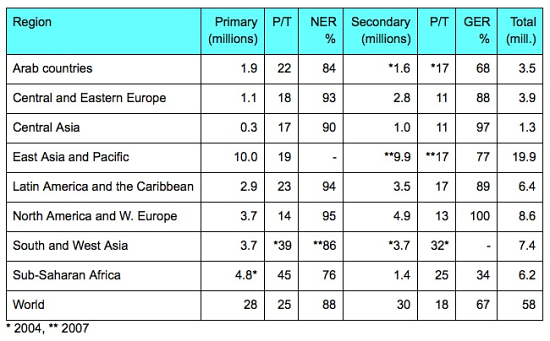

Let us look at the numbers, some of which are collected in the table. For OECD countries there are around 16 students per teacher in primary education (CESifo DICE Report). Looking at the numbers, we can take a national average of 15 pupils/teacher as the norm for primary education in developed countries and 13 for secondary education. But note that these are just very global statistics on education. And keep in mind that worldwide, approximately 100 million children that should be in school are not.

Furthermore, as these statistics are global, they do not tell us how the available teachers are distributed. The developed countries are able to organize education in such a way that all children have comparable access to education. The difficult situations in the developing world make that the already low number of teachers are also distributed unequally. The pupil/teacher ratio can be much higher in rural areas than in urban areas. So for many children, the situation is even worse than these averages indicate.

.

Teaching staff in millions, pupil/teacher ration (P/T), and enrolment ratios in percent (net- NER and gross- GER) in primary and secondary education. Data for 2008 unless indicated otherwise. Source: Unesco

Just to get the average number of teachers in the developing world to the level of that of the developed world would mean that the number of teachers in Sub-Saharan Africa and South- and West-Asia must more than double. In other regions increases of over 50% would be required.

To get these numbers in a global perspective, there are currently some 58 million teachers in the world, 28 million in primary education and 30 million in secondary education (see table). If the worldwide average ratio of pupils to teachers should be reduced from 25 to 15 for primary and from 18 to 13 for secondary education, an extra 30 million new teachers would be needed (19 million in primary, 11 million in secondary education).

Even a more modest aim to get the pupil to teacher ratio to 20 in primary education and 15 in secondary would require some 13 million new teachers, world wide. And that is without increasing the enrolment ratios in primary and secondary education to 100%. That alone could require another 20 million teachers.

In conclusion, any attempt to improve education in the world by increasing the number of teachers must prepare to recruit, train, and deploy well over 10 million new teachers, and maybe even up to 50 million new teachers. Trainers are needed to train these new teachers. If we are in a hurry, we would have to train them in, say, 6 years for a 3 year teacher training program, that would make 4-13 million new teachers a year entering training. This training program would require anywhere from 130,000 – 400,000 trainers for these teachers.

Round numbers:

13-35 million new teachers: Recruit, Train, Deploy

40 million teachers: Retrain

150,000 – 250,000 trainers for these teachers

Can we really rely on training more teachers alone?

Obviously, the numbers given above are rough ballpark estimates. But it is clear that “invest in teachers and schools” often means “double or triple the number of your teachers”. A truly gargantuan task.

There is an important question that has to be answered before such an effort is undertaken.

Why is it that there are not enough teachers in the first place?

It is not that training teachers is an unknown art. Teachers have been trained for a century now. Why is the world short of tens of millions of teachers?

It is not for a lack of trying. Ever since development aid became into existence somewhere after WWII, it has been known that more teachers are needed. But somehow, the developing countries have been unable to supply them. There are many reasons for this shortage, underfunding, bad working conditions, labor migration away from rural areas, competition from other employers, low social status, bad organization etc. These are social problems. And we know that social problems are the hard problems. And there are as yet no convincing ideas on how to solve these very hard problems.

So, that is why I think any plan to “invest in teachers, not technology” is bound to fail. There is simply no known policy that can solve the problems that plague teacher recruitment and training in less than a generation, if they can be solved at all. Trying to recruit and train millions of new teachers is simply going to fail. Any attempt to just throw money at the problem will fail just as badly as all the other cases where a solution was dropped on the developing countries.

I like the idea of supplying every child with a well trained teacher in a class with only 30 pupils. My sole objection is, it cannot be done. And even if it could be done, what should be done for the children that enter and leave school in the meantime?

Technology to the rescue

Compare the problems of supplying children with teachers to supplying them with technology. If we would supply the roughly 900 million children in dire need of education with OLPC laptops over a period of 5 years continuously, this would cost around $40B a year, worldwide. (200 million laptops a year at $200). I can write a small encyclopedia with all the objections to spending $40B/year on OLPC laptops. But we all know that it is actually possible to produce and distribute 200 million laptops per year. It costs money, but it can be done. This is technology, and technology is easy.

As education will have to rely on the existing workforce for the foreseeable future, their work, and that of their pupils, should be made as easy and productive as possible. In a service industry like education this means using technology, i.e., ICT. But we should not forget that a lot can be done using less glamorous technology. For instance, in many regions in the world, a bicycle may improve mobility of children and teachers alike and enable children to continue further education (Indian Times, 2009).

Without light and heating, education would have to be curtailed severely during the winter in my own country. But such measures, e.g., electrification or increased mobility, have obvious positive impacts on economic development. Such measures do not have to be argued. Here I would like to concentrate on ICT4E, the advantages of which are much more contentious.

ICT4E has the same problems as ICT4D(evelopment). It is inconceivable that a solution to every local problem could be devised by a person sitting behind a keyboard in Western-Europe. People on the ground, locals, know what is needed and what is available. Bicycles can help some children get to school in the Netherlands or regions of India, but it would be a complete waste to send bicycles into other areas, e.g., the Andes or Himalaya. However, there are many “simple” problems that crop up everywhere in the world, and might be solved by a single tool or technology. Just like the blackboard solved a problem experienced in every classroom in the world, there might be technologies that are valuable everywhere.

In our quest to look for eligible technology, I would like to stick to ICT solutions that avoid the “Top 7 Reasons Why Most ICT4D FAILS” (Rogers, 2010, a nice YouTube movie). The video explains it all so I will not repeat them here.

.

The central question is how to make ICT useful for schools. Received wisdom is that technology should be integrated in community life before it can be really useful. It is instructive to study cases where this received wisdom has been flouted. Prime examples are radio, television, and mobile phones. History has shown that these gadgets have been embraced by almost all communities, even those that lacked any understanding of the underlying technologies. In a completely different field, the simple formulation of Oral Rehydration Therapy helps local staff tackling one of the leading causes of child mortality in the developing world without lengthy training or expensive infrastructure.

The successful electronic consumer gadgets all have in common that they require zero maintenance and are robust in normal use. The only consumables of the gadgets are electrical power or batteries. A costly infrastructure is needed for all three, but this is both outside of the view of the consumers and the costs are shared by all.

These technologies fitted every human society because they were transparently enabling some of the most basic human needs: Exchanging stories, gossip, and news and playing music. This acceptance is not a matter of User Interface or ease of use. Text messaging on a mobile phone must count under the worst User Interfaces ever invented. But because the feed-back is immediate and transparent, even small children are able to put up with it (and often can do the task blindfolded).

So we need turn-key drop-in technologies that have zero-maintenance, are robust in the field, including fields of the green and grassy type, and latch into basic human behavior. Mobile phones might be the best examples, as they require little more than electricity and a (prepaid card) number. They are easy to carry and protect: Just keep them out of the rain or in a pouch. And they help people to do what they seem to like most, talk and write to each other.

A last feature of successful technology introductions is a long technological horizon. Anything that takes so much effort to introduce should last a long time. We can expect our children to still use something that functions as a phone or a TV. The actual device might look different, but we should be able to recognize the function. Especially in education, new technology should last a generation. The children of the pupils that are introduced to the new technology should be expected to use something alike. So if no continuous upgrade path is expected over the next decades, I think the introduction of a technology should be seriously reconsidered.

To summarize, the kind of technological solutions that I am looking for would fit all of the following (think radio, TV, and mobile phones):

- Solves a global problem or need

- Robust in normal daily use

- Turn-key drop-in

- Zero-maintenance

- Consumes only electricity, and very little of it

- Connects to content or communication channels (including surface mail)

- A long technological horizon

Note that the technological solutions discussed are intended to solve serious problems. Nowhere is it assumed that technology should improve education if there are no real problems. Technology does not replace a teacher, but it can help her teach and help the children learn.

My archetypal example of successful educational technology is the blackboard. The blackboard solved a huge educational problem in teaching for large groups: A simple, flexible, and cheap method to present text and diagrams to large groups of pupils. It allowed to effectively display and explain complex concepts so that children in the back of the classroom could see them too. It is a pity that you need chalk to write (a consumable), but that proved surmountable.

Two examples will explain these bullet points: The pocket calculator and desktop PCs running Microsoft Windows.

Pocket calculators, or better, graphical calculators, were introduced in secondary education in Europe at the end of the 1970s. The problem they solved was that some important mathematical concepts could not be taught because the calculations on anything but toy problems were too cumbersome. With these electronic calculators, realistic problems in statistics, matrix algebra, and function theory could be introduced into secondary education. As these calculators can be used in class and at home, their use can be easily integrated into the relevant courses. Moreover, pupils learned how to perform arithmetic on real calculators like they would need in working life later.

So using the calculators solved a small, but very real problem in the teaching of mathematics, economics, and science. Obviously, a pocket calculator fits all of the other bullet points. They run for months or years on a single battery, get their contend from the text books, and they have been in continuous use for over 30 years now. A clear success story.

On the other hand, desktop PCs in school running Microsoft Windows defy every bullet point. The only general problem that is solved by a PC in school is Internet access. But there is little use for direct Internet access in class. Desktop PCs can be used in courses directed towards computer use, but even that is hardly useful in school. At home, PCs do have general practical value, but that has little to do with the limited presence of PCs in school. Introduction of such desktop PCs in schools in the developing world generally ends in a deception.

An important problem is that Microsoft Windows has a tendency to break in daily use, especially when the computer has an Internet connection. The hardware of desktop PCs is not designed for a tropical climate. Moisture and dust can easily break the hardware. Installation and maintenance are difficult and require special skills and knowledge. Desktop PCs consume a lot of power and, therefore, cannot run on batteries. So their use is very limited in locations with unreliable power supplies. Connectivity is good, if a wired or wireless Internet connection is available. And they can be used with CD/DVD disks or USB memory sticks.

The technological horizon is more complex to judge. In future generations, we can expect to see screens, keyboards, and computers of some kind. However, I still remember a quote from a parent in the 1980s. When asked why she preferred the use of MS Dos PCs over Apple Macintosh computers in primary school she answered “Because when my child will go to work, it will have to use MS Dos, and not the fancy graphical interface of the Apple Macintosh” (paraphrased from memory). And it has been this way ever since.

If we look at the developments of computer use in the last years, we see perpetual shifts. Nowadays, the shift is towards a completely different model of computing with the integrated User Interfaces of mobile phones (iOS and Android) becoming the standard for tablets, netbooks, and upwards into other computers. So the technological horizon of standard desktop computers has always been very short.

An example of new technical gear: The OLPC XO

.

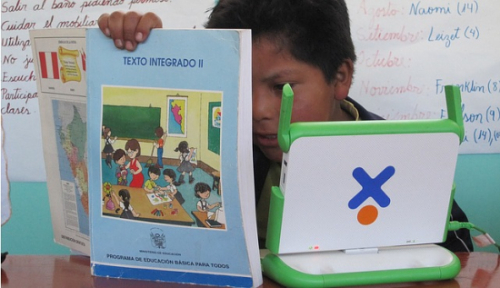

As an illustration of a recent project, compare the above with the OLPC XO laptop. The design goals of the XO laptop came very close to the ideal of a no-worry drop-in technology.

The software is distantly related to the Android mobile phone operating system with a zero-maintenance update and security model. The laptop was designed to be robust and the only consumable was electricity. The laptop was easy to carry and protect. It enabled access to the Internet for video and voice connections, email and Instant Messaging, and you could also use it to play music. Connected to the Internet, it could replace radio, TV, phone, and music player.

The laptops could double as book readers and store a complete library, allowing schools that could not even afford textbooks to get a library for each child. On top of it, it could also be used as a computer. The technological horizon looks promising as some kind of small, mobile computer with a simplified interface is likely to be around for the next decade or so.

What went wrong with the first version of the XO laptop?

Basically, the execution fell somewhat short of the design goals. Quite a number of laptops were rolled out before the software was finished and these laptops suffered from a lot of very annoying bugs. These bugs could not be solved by the normal update mechanism, but required replacing the operating system itself. The logistics of supplying a new operating system image to laptops in the field proved to be impractical.

On the hardware side, the keyboard was not robust enough and broke in too many laptops, as did the trackpads. And power consumption was still a bit too high for many locations. The mesh network to share Internet connections did not scale well inside schools and did not deliver the planned connectivity. Supplying Internet connectivity to schools proved to be the Achilles heel of the project. And without an Internet connection, the laptops became much less useful for their intended purpose.

In then end, the first generation of the OLPC XO laptops came very, very close to achieving the status of a no-worry drop-in technology. And where there was Internet, they seem to function as intended. But without a solution for the Internet connectivity, the laptops are much less useful. Had there been Internet connectivity at home, we can be pretty sure that the children would have found out how to use the keyboards and navigate the User Interface. If primary school children can find out how to send text messages on mobile phones without formal instruction, they can learn to use the OLPC’s Sugar interface.

But even if the XOs function as intended, there remains the logistic problem of giving out and replacing laptops and delivering electricity and Internet connectivity. In general, all technological solutions require logistics to distribute the gear (TV sets, mobile phones), the electricity (or batteries, or solar panels), and the connections (transmitters, cell towers). These will always be a problem for rural areas in the developing world. But these factors affect each and every attempt to solve problems in the developing world as they are at the heart of the economic under-development to start with.

As many technophiles, I really love the OLPC laptop. But I know that was not the question. What we really want to know is whether there is a technology that solves the problem at hand. However, this discussion is targeted at a global audience, and we know that the cost of technology depends on the production volume. The very first radio was extremely expensive, the billionth transistor radio is a free promotion item. So I will look here at global problems with high volume solutions.

Example of a global problem and solution: Textbooks fantasies

.

To illustrate the ideas presented above, I will fantasize about a real global problem in education and a technological solution.

Textbooks are a necessity in school, but they are expensive. My country spends around 300 euro ($400) a year per pupil on textbooks in secondary school. For this money, each pupil could get a laptop and a broadband Internet connection at home for the duration of her education. With some change to spare for electronic textbooks. Most of this cost is the result of monopoly rents by the publishers, as it is in many developed countries. But even at half the price, each student could get an ebook reader with a lot of money to spend on electronic books and prepaid mobile Internet.

The root of the textbook problem lies in the cost of production. Textbooks are a difficult market, with high investments in writing and printing and high distribution costs. And it is an all or nothing market. Either your book is selected for the curriculum, and you sell big, or it is rejected and you sell nothing. Moreover, to stay up-to-date, textbooks have to be revised very often. A lot of insider knowledge is needed to produce a textbook that fits in the standard curriculum. As a result, the market for textbooks for primary and secondary education is always limited to a single school system (country).

And in the end, the textbooks are not that great at all. Ansary (2004) gives an illuminating and entertaining, but also infuriating, account of the way text-books are produced in the USA. Quite often it is a pain to use these textbooks. Most teachers have to create extra “cheat-sheets” to supply missing material and explain incomprehensible portions of the text. Beyond all these problems with the content, there is the daily wear and tear of paper books that makes every textbook usable for only a few years, if well cared for.

In accounts of classroom practises in the developing world, we often hear of whole classes that spend their day copying the complete text of a textbook from the blackboard into their notebooks. This seems a waste of time. When copying large amounts of text, you are unable to think about the text or even remember it. However, supplying the books themselves to the children was obviously not possible. So copying a book wholesale might be the only way the children can ever get hold of the text. Still, we will all agree that it would be better if the pupils had the same textbooks as the teacher. The teacher could then spend her time explaining the material in the textbook and children could spend time learning and practising the skills covered by the textbook.

So here we have a truly global problem: Expensive, outdated, low quality, and cumbersome textbooks that are often not available for the children in the developing world. Can we fantasize about a better system? One that gets both teachers and children the books they so desperately want and need?

There is a very good idea that was actually embraced by (some) politicians in the developed world, the Open Textbook Initiative. Creative Commons electronic books produced by authors and teachers in Wikipedia style (Creative Commons, 2010; Beshears, 2005; Durbin 2009). In principle, this can be applied world wide. The ministry can give grants for writing specific electronic textbook, or volunteers and teachers can write their own. The textbook are licensed under some Creative Commons license that allows free distribution and adaptation. The books are archived and made available in a repository and distributed electronically as ebooks.

Teachers, scientists, and students can add and submit changes in Wikipedia style. It cannot be said that ebooks are better than paper books, but they will be preferred over no books at all.

And the costs? As I wrote above, for what the developed countries pay for textbooks now, they can supply top of the line ebook readers and Internet connections to the students, and have massive amounts of money to spare for grants to write the books. And if you ever tried to lift the school backpack of a high-school student over here, you know that ebooks would take a heavy burden from their shoulders.

In the developed world, the Open Textbook initiative solves kind of a luxury problem. The developed countries can actually pay for the costs of over-priced paper books. They just feel they do not get quality for their money. And often no quality at all. The question is, could such an Open Textbook initiative work in the developing world, where paper textbooks are problematic?

Here we have to look again at our technology bullet list. The Open Textbook initiative does serve a pressing need for good and affordable textbooks. We can be pretty sure that every teacher in the world would welcome better, up to date, textbooks. So, provided a collection of good textbooks can be produced by way of government grants or volunteer work, this part is covered.

Current ebook readers are constructed for indoor use in the developed world. They do have too many unprotected openings and fragile components for a developing world environment. However, covering up these holes and putting in more robust components is not very difficult, the OLPC has done most of that work already. For most ebook readers this would be a minor, and cheap design change, not a problem.

The use of ebook readers is quite simple. You drop in an ebook (or a shelf of ebooks) and you start turning pages. Apart of language and date and time there is not much to set. So, indeed turn-key drop-in technology. Theoretically, you can update the software of an ebook reader, but there is not often a need for doing that. An ebook reader can in most respects be considered to have zero-maintenance.

And last, but not least, ebook readers using electronic paper displays have extremely low power use. Their requirements are low enough to make charging with small solar panels feasible. Current retail costs for cheap ebook reader offerings are below $100 for consumers. Ebook readers cannot be repaired (easily) in the field, so any program to supply them should stock for replacement readers.

The next bullet point is connectivity: How to get new books on the ebook reader. Ebooks can be transferred to an ebooks reader by either connecting it to a computer which has them stored or downloaded, or over a wireless connection in the more expensive ebook readers. Most readers have a slot for external memory SDcards, which could be used to distribute ebooks. Even though SDcards might be rather fragile in daily use, they can be distributed over surface mail. So, the connectivity could be handled by sending USB sticks or memory cards with the mail or a messenger. There would have to be some outlet with a computer or laptop to transfer the new ebooks.

Sounds ideal, so why has it not been done yet?

Even at $50 a piece (gross price), a complete roll-out would be a rather big investment for a single purpose gadget. The cost would exceed the total educational budgets of many countries by a large margin. And the organization of a coordinated roll out of so many devices could overwhelm the capacities of most administrations. The cost and organization alone of an ebook reader roll out would exceed the resources of the countries that need them most.

Furthermore, the technology is all very new. If you roll-out ebook readers today, you might miss out on the powerful and cheap tablet computers of next year. A kind of, very realistic, economic deflation fear. So the technological horizon is short, very short indeed with all the new tablet computers coming out. Ebook reader apps are already part of every new smartphone. In a few years time, separate ebook readers will cease to exist and a general mobile platform will have taken over their function.

There is also the chicken-and-egg problem of needing electronic textbooks to use an ebook reader in class, while these textbooks will not be produced if the children have no ebook readers. On the other hand, if there is one thing that can be learned from the history of the World-Wide-Web and Wikipedia, then it is that if there are readers, the writers will come. The real challenge is to get a national Open Textbook initiative going. This will be addressed in the next section.

Teaching the teachers: A program fantasy

.

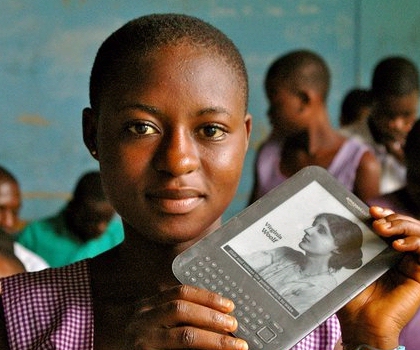

From the earlier discussions on Educational Technology Debate, it has become quite clear that the real challenge is not to get cutting edge ICT4E gear in the hands of the children. The real challenge is to ensure that the teachers are able to actually make use of the technology in their lessons. The solution is simple to formulate: Remedial courses for the teachers. But the initial problem was that it was not possible to adequately teach the children. How can we then train the teachers?

First of all, there are much less teachers than children, and they can occasionally travel. So it should be possible to arrange some classes in (semi-)urban areas where it is easier to provide education for adults. On the other hand, children have ample time for learning, adults have other responsibilities. So any courses for teachers must be short, targeted, and effective. The main point is that a one week course during the summer break will not be enough to prepare for a large change in the curriculum including hitherto unseen technology. And for teachers too, it holds that education must be interactive. Simply dumping a large amount of documentation on them will not lead to them actually mastering the subject.

Let us assume some technological solution has been selected for a nationwide roll out. For the sake of argument, our fantasy ebook reader program is introduced in schools which lacked books. The ebook reader program is accompanied by a national Open Textbook program. Now, what follows is my fantasy of a teacher instruction plan to use these ebook readers. It is assumed that the Ministry of Education can hire some local (or international) educational experts to construct a basic curriculum and lesson plan for use with the textbooks on the ebook readers. These plans are the basis for the textbooks.

The current practise is that teachers do group drill exercises, e.g., children copy the teacher’s text book from the blackboard and memorize some part of it. Such drills normally would take most of the in-class time. The task of the training program is to instruct the teacher how to operate and use the technology itself. They should learn how best to teach the children the use and care of the technology. But this introduction to the technology is just the basic part.

The real training must be to instruct the teachers how to use the electronic textbooks in class. As copying and memorizing the text books has become an irrelevant exercise, there is time during class to do other things. So teachers will have to get an idea what these textbooks can be used for. The curriculum will be adapted to reflect the presence of the ebook readers. As other commenters have already remarked, this is not something that can be achieved in a mere 1 or 2 week course.

The solution would be some kind of continuous distance learning program. Any one-time out-of-town courses should be followed by refreshers over correspondence. This could be anything from surface mail of course materials and assignments, special magazines, to special (off-hour) radio and TV programs, phone-in sessions, and if Internet is available, live Internet chat or video conferencing sessions. Given that the whole program will cost quite a lot, a special, one time a week radio or TV show will not be that expensive. Tapes can be send to those who cannot listen or watch life.

For our ebook reader program, the reading and audio materials can be mailed on a USB stick. We can nicely integrate the distance learning course with the Open Textbook initiative. Instead of dumping the textbooks on the schools, it would be nice if the teachers would get a say in what would become part of the textbooks. So, part of the assignments could be to suggest improvements to the textbooks. Maybe write or edit paragraphs. And send back the notes. Nothing fancy, pencil and paper would already be enough. These notes can be processed by the editors of the textbooks. Best to keep a list of contributors at the back of the final textbooks.

Obviously, there is not a lot that can be done in the one to two years in the run up of a large roll out. Especially as the teachers will have their normal responsibilities and duties, which would already take up their time. A course with associated book, magazines, and radio and TV programs would probably be the best option.

This is a format that is used world-wide for teaching languages. There is a lot of experience with such TV/radio courses. The exact formulation will obviously depend on local circumstances and customs. The real advantage of such a program is that it can be produced and staffed by locals. Teachers “on the ground” can be interviewed, and radio shows can contain phone in question and answer sessions as well as listener feed-back. This is all quite ordinary practise in most countries.

It would be unrealistic to expect that all teachers will have opportunity and time to fully participate in the interactive and collaborative aspects of such a program. But the more teachers have a chance to be active in the program, the better it will take root. And for teachers too it will hold that peer instruction is the second best thing after teacher instruction. So if the program can reach a large fraction of the teachers, we can hope that their knowledge will diffuse through the whole community. And there is no reason to stop the information program after the roll out is completed.

Discussion and Conclusions

.

It is obvious that developing countries will not be able to double or triple their number of teachers in the short term. So for the next decade or so some solution will have to be devised and implemented to improve education for the children entering school. Beyond more teachers, there are only few options left. Technology is one of them. To increase the chance that the chosen technology will actually be effective, some precautions should be taken. Basically, the probability of success will vastly increase if the technology can be used and maintained by children for the intended purpose. Which is basically the main aim of the small bullet list above. Anything more complex or demanding risks being relegated to gather dust in a corner.

But after we have the wonderful gadgets and gear, it should improve education. As teachers will have to change their teaching habits, it is very advantageous to instruct them in using the technology to improve their lessons. Given the other obligations that occupy teachers, any face-to-face training courses have to be short. To make the changes permanent, an interactive follow up is needed over the months that follow the face-to-face courses. A large number of options exist for semi-interactive distance courses and follow ups: magazines and tapes in the mail, radio and TV with phone-in, or question sessions by mail or phone. All these are distance learning practises with a long history. Only think of all the language courses broadcast around the world.

Under-development and over-stretched schools have shown to be very hard problems to solve. Although some kind of technological progress will be involved in the eventual solution, it is still unclear whether introducing any single technology can actually help. But as technologies like radio, TV, mobile phones, and even Oral Hydration Therapy have shown, the dire effects of important global problems can be alleviated by introducing certain types of technology. With only limited instruction, I think it will be possible to find solutions to help alleviate some of the educational problems that result from a chronic shortage of qualified teachers in the developing world.

References

Ansary (2004). A Textbook Example of What’s Wrong with Education: A former schoolbook editor parses the politics of educational publishing, Tamim Ansary

Beshears (2005). The Case for Creative Commons textbook, by Fred M. Beshears, U.C. Berkeley, April 07, 2005

CESifo. Class size and student-teacher ratio, CESifo DICE Report 4/2009

Creative Commons (2010). Open Textbook,

Durbin (2009). Durbin Introduces Legislation to Make College textbook more Affordable (press release)

Huebler (2008). International Education Statistics, Analysis by Friedrich Huebler, Pupil/teacher ratio in primary school, Pupil/teacher ratio in primary school

Indian Times (2009). CM gives Rs 15,000 and a bicycle each to girls, Feb 4, 2009

The Times of India (2009). India has one of the lowest teacher-student ratios: Expert,, Nov 7, 2009

Rogers (2010). Top 7 Reasons Why Most ICT4D FAILS – Dr Clint Rogers

UNESCO. Table 11: Indicators on teaching staff at ISCED levels 0 to 3, (accessed 02022011)

Realistic and inspiring. I would like to add the information of the McKinsey Report (http://www.mckinsey.com/App_Media/Reports/SSO/Worlds_School_Systems_Final.pdf)

which found decreasing the size of the classroom did not improved educational perfomance as much as increasing teacher quality. So actually increasing class size with better teachers could be a good solution. Anyway your point is clear, better teachers is, at best a long term solution, ICT gives an opportunity of improving while waiting.

I do not intend to be overly negative here. I enjoyed reading the first third of this post. However, then I came to the part that contained the following: (the next three paragraphs are copy-pasted from above)

These are social problems. And we know that social problems are the hard problems. And there are as yet no convincing ideas on how to solve these very hard problems.

Any attempt to just throw money at the problem will fail just as badly as all the other cases where a solution was dropped on the developing countries.

It costs money, but it can be done. This is technology, and technology is easy.

So, as I read the rest of the post, I couldn’t help thinking that what was being proposed therein was to use (easy) technology to address (or avoid addressing) the very hard social problems.

I have to argue that throwing easy technology at hard social problems doesn’t work, and I don’t understand how doing so differs from other cases where a solution was dropped on developing countries. The hard social problems have to be addressed for technology to be effective.

"So, as I read the rest of the post, I couldn’t help thinking that what was being proposed therein was to use (easy) technology to address (or avoid addressing) the very hard social problems. "

That was most definitely not my intention. What I tried to say was that the global teacher shortage is a very difficult social problem. A problem we have yet to see a solution for. And even if we start to work on solving it today in force, it would still take decades. So what can we do in the mean time for all the children that are entering school now, well before we have all those qualified teachers?

My suggestion is to look for help in technology. Because we know that if we can help the existing staff and their pupils to improve education now with technology, even if it is a little, then the benefits would be large. And if we find a solution to some of the challenges encountered by staff and pupils, then the technological aspect will be the easy part.

So, my quote is that technological problems are easy, almost all of them, compared to social problems. Which means that technological solutions will arrive faster than social changes. And that is important, because we are not here to solve the social problems in the educational system (however worthy that would be), but to improve education for the children.

(cross-posted more or less to http://www.natomagroup.com)

Here's another way of looking at the challenges of increasing the supply of trained teachers.

In many countries, rural schools have few students [ok there are a lot of factors in play in these situations]. Small numbers of students is one reason that multi-grade classrooms are so strongly supported by donors, and by some ministries of edu.

Analysis of this situation as it plays out in Indonesia suggested that many classes in rural areas were unsustainably small. And that teachers in those schools were poorly educated and trained. These observations led to the 2005 "teacher law," requiring that all teachers have a 4-year degree and promising that those teachers would receive double the current pay (with an additional 50 percent increase if they agreed to a posting in a remote [not rural, most of Indonesia is rural] area).

These teacher-focused measures demonstrate how unintended consequences can mar even the cleverest efforts.

Enrollment in schools of education is rocketing because the potential pay for teachers (especially if you sign up to work in a remote area [another story, which I hope someone else addresses]). One professor explained to me that his school would graduate about 200 Teachers in 2009, but none of them would be placed in government schools.

Part of the problem is that management of the schools themselves is split between the central government and the provinces (as a result of radical decentralization following the end of the Suharto dictatorship).nas in many systems, the central govt simply can't trim its teacher corps as it would like.

But the simpler problem is also the grander problem: by increasing teachers' pay, MONE increased the supply of new teachers, while its efforts to increase class size (and decrease the number if teachers overall) has effectively reduced demand for teachers. If these new graduates were commodities, we'd call the phenomenon an inventory surplus; as it is, we can call it policy-generated structural unemployment.

What's interesting about the problem, from the POV of Mr Van Son's post, IMHO, is that it demonstrates that once one starts making changes in teachers' employment necessary to improve a national teacher corps, one is messing with employment conditions and career choices in a large sector of the economy, one that exists in relation to _other_ sectors of the economy and to the jobs therein.

For a terrific and far-more detailed analysis of the situation–and a good example of impact analysis of policy in general, see "the economics of teacher supply in Indonesia" by Dandan Chen of the world bank, available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_i….

My "global analysis" of the teacher numbers is not even a start of a real treatment of the problems in education. It only points out the "logistic" problems of recruiting and training new teachers. These logistic problems are mind boggling, but they still hide the underlying social and labor questions.

You rightly point out that the real question is "Why is there a teacher shortage?".

This is a labor market and policy problem, linked to the expensive nature of high quality service industries, i.e., with highly educated employees. Obviously, if education is withdrawing large numbers of educated laborers from the private sector, this will affect other sectors of the economy. It would be rather counter productive if staffing the schools in, e.g., Indonesia, would lead to the collapse of the manufacturing industry, putting out of work the parents of the children taught by the new teachers.

Someone else remarked on ETD that trying to hire more teachers in India by raising their wages would attract the very people you do not want in front of the children. The social roots of these problems are very complex and I feel completely unqualified from even trying to analyze them.

My intended message was simply that even if we would be able to solve these social problems in recruiting teachers, it could take the world decades to actually get the required numbers. So, whether or not the developing countries will be able to recruit sufficient numbers of new teachers, they still need to improve education of the children entering school until this goal is reached.

I did not read through all of the article, so I apologize if I do not do the article the justice it merits, but quoting a speaker at Doha's WISE 2010 Summit "we need a wall-mart effect rather than a boutique effect" referring to a teachers' numbers curve, denoting we need to reach as many teachers as possible. My point of view is that we have between 300,000 to 1,200,000 teachers across north of Africa. Using a successful, cost effective, 1 dollar / student model, I designed model that can reach 100 million teachers and youth across MENA region in five years. Taking Jordan as an example, we have 1.5 million students. If I target only 25% of the teachers, it means that I am sending unprepared souls into a saturated market that does not offer ample job opportunities to start with, let alone for unskilled school grads, or post graduate adds, that still lack the ‘needed skills’. The way I see it, by using and applying national training, promoting ownership, heading a sane policy plan and vision, chances are we pull it through. I also found out that one computer school lab per school or village (group of schools), can go a long way, if properly used. However, I admit that connectivity is crucial, but clever logistics help. Using this model, I have trained 10,000 teachers in the Arab world, with 1 million students reach, that is when I realized, that we are going too slow, and people will suffer in millions in the meantime, so I scaled up the model for 1000 teachers to 10,000 teachers, using certain steps, and it can be applied to 100,000 teachers simultaneously as 3rd phase. .

I see your point, and I agree with you by doing with what is available rather than go for the impossible: policy makers or implementers get touched with what they see, each developing country has “one” or more “missing” or weak ingredients, if we look at the issue from a global perspective and try to find common basics, we can go a long way.

It is possible to have a qualified teacher gradually, in front of each class, normally, between 30 – 40 students in developing countries, where some public schools have up to 20 sections or more, from the same grade, and some, diminishingly, have 2 – 3 day shifts (over-crowdedness), and some schools still have no ceilings.

Also, with respect to the ratio, if we are targeting public schools reform, I prefer to use teacher per student ratio inside the classroom, because for every child inside the school, I found out in some countries, there is at least one, if not more, outside the school system. This is another problem all together, falls under EFA initiative I suppose, how to increase enrollment. On the contrary, I think using group models, can help manage such classes, eases the burn off the teacher’s hand as it changes behavior from instructor teachers to facilitator teachers, and students become interactive learners. You don’t even need ICT or IT or any kind of technology for that matter. In my opinion, it’s 90% knowledge skills and 10% technology, because technology is ONE Of the tools sets. There are so many other resources that can be used to promote such upper order skills, of course, I agree with you, nobody would say no to a “perfect” situation, where everyone has a teacher and accessibility !

I also agree, for educational reform to work, the basic ingredients, in this simplest form has to be there. One of them is building schools, re-distributing school locations to safer areas, and of course, creating teachers motivation systems to attract more teachers into the system, financial or other, alongside policy, vision

..continued

, creative financing, ICT infrastructure, teachers training programs, curricula, …etc

Considering Arab countries spend by the far the most among countries, therefore, it is also always feasible to increase / train teachers , It’s a problem of mismanagement in the Arab countries, more than a financial issues. Wayan and I saw dear resource’s and so much spending on one item that was not functional so spending is not an issue as much as “making it work”

Another problems is that we need in increase students enrollment, which doubles the ‘low number of teachers’ problem. Again, we managed to achieve astounding results, despite all odds. We managed to change the classrooms dynamics and the best skilled students our limited resources could yield.

Again, on the number of teachers, I would chose to look at the available teachers quality. 100,000 teachers may well equal 50,000 / i.e. counting the effective ones, hence the ratio of teachers: students drops down, hence a more reason for focusing on training existing teachers. Happy teachers, well skilled can attract others into the profession.

It’s more feasible to enhance capacity of existing teachers, rather than incorporate and train new ones. There’s simply no enough funds and almost imposible for some countries, however, no trainers are necessary needed to train teachers, the model I tested and tried, starts with one trainers (and yields a sustainable cascade training yielding 1000 teachers, 20 core trainers and 40 master trainers, with 200,000 students reach. The system offers mentoring and quality control, results were positive and students registered advanced online and other output results.

True, teachers training is an ancient habit, but that is all called now “traditional” and old training with so many drawbacks. It is essential to start over. Again, knowledge economy and upper order skills or some call it 21st century skills or future skills..is all about the MIND SET. I like to refer to the process of training teachers as: “to train teachers on creative, critical, analytical thinking, solving problems, working collaboratively in groups, having advanced communications skills, then I add : THE ABILITY to identify and search for available resources and tools, ONE of which is technology. So, technology is JUST a tool, a power one nonetheless it remains ONE of the tools. And tools includes lesson planning, self-assessment, rubrics, presentation skills, etc etc…so a teacher can go a long way WITHOUT technology, or with a smile device, be it just one mobile, or digital camera or printer…or once a month trip from the village to a city computer lab !!!

What is the minimum amount of technology needed ? let’s go for the minimum than can yield ‘students of the future”: results showed, that as little as ONE computer lab, in a village of 5 schools can go a long way. But ideally, magnificent results can be attained by having ONE computer lab/ school. COW (computer on wheels) can also be sued, or multi-purpose rooms with as little as on PC and projector. Kids are amazing at using resources and self-learning (take the hole of the wall example, I was fortunate to meet its inventor).With minimum technology, I saw the poorest of schools, with HARDLY any resources win a robot competition by feeding programs to microchips LEGO models and creating alternative to energy.

…continued…sorry for being lengthy, but you did bring many valuable points to the table, and you addressed the issue from many angles: …

I also prefer, based on the Japanese educational goals back in late 90’s, not to use ‘label programs’ but to create their own.

I thank you for your input, but zero-maintenance for technology is not possible, anti-virus contracts, for one are needed, and an automated reporting error reporting systems. Actually, it is more important to have a ICT maintenance system and building the system itself because teacher and students would lose faith and investment on IT purchase is lost.One option would be to have decentralized school-based technicians and systems.

Dear Reem N Bsaiso

Thank you for your extensive response. I think I can agree with almost everything you write. My contribution boils down two two points:

– Please increase the number of teachers and their quality, but note the enormous scale of the task

– While we wait for all these new and qualified teachers, do something NOW to help those in school

On the last point I suggest to take a very good look at technology as a way to help teachers and children in school NOW.

It is here that I want to make a remark on your comment. You write:

"I thank you for your input, but zero-maintenance for technology is not possible, anti-virus contracts, for one are needed, and an automated reporting error reporting systems."

I disagree. First, the OLPC (with Bitfrost) showed the theory behind computer security was viable, and both Android and the iPhone proved this in the field. Mobile Smartphones are simply computers, and they lack user serviceable AV or other malware protection. That is what I mean with Zero-Maintenance at the local level.

"Actually, it is more important to have a ICT maintenance system and building the system itself because teacher and students would lose faith and investment on IT purchase is lost.One option would be to have decentralized school-based technicians and systems. "

Any such ICT maintenance system should be invisible to the end-user/school. No-one is worrying about how the iPhone or Android app stores manage security. We all know it happens, but that is not our concern. The same with the OLPC installations.

Please forget everything you know about MS Windows maintenance and security. It never worked. Nothing you learned from MS Windows maintenance can be applied to Sugar/RedHat, Android, nor iOS (iPhone). And in the end, you hardly need to know about how it is done as an end used.

please make the discussion relevant to our existing problems.

GM

Hello, and thank you for this very exhaustive discussion of the challenges posed to scale up the numbers of teachers needed today. First of all I completely agree with the basic premise–that technology offers a partial solution to help us fill the teacher shortage. As an educator of 24 years I have learned that the greatest resource for teaching are the students. Our educational models are from a 19th Century Prussian industrial model. It is silly to replicate this today, or perpetuate its use. So I would suggest that the solution to the teacher shortage is that we are asking the wrong question. We cannot solve the problem with the same thinking that created the problem. The teacher standing in front of the class is archaic and based on power and conformity–not learning. Our understanding of how we learn, and how the brain learns is clear–listening to a lecture engages only 5% of our facilities. Lecturing is not teaching, and listening to a lecture taking notes is not learning. 95% of learning occurs teaching! Ok, we have hobbled along this path of 'sage on the stage' from the legacy of the middle ages and the monopoly of knowledge that was held by the privileged or priestly caste–and this was adopted by our secular institutions. The result has been the disconnect from our environment and plunged us into the crisis we face as a species. I'm sorry, but science got it wrong.

ICT gives us a new opportunity to empower the students to become teachers. In the thread above from Reem N Bsaiso, "I think using group models, can help manage such classes, eases the burn off the teacher’s hand as it changes behavior from instructor teachers to facilitator teachers, and students become interactive learners" the idea of teacher as facilitator emerges. This is the direction to go and solves the teacher shortage problem–if you empower the students to become teachers. This in turn would create a way for, "creating teachers motivation systems to attract more teachers."

There are new economic models to assist this, namely mobile micro payments for students who distinguish themselves as 'Peer to Peer' teachers and the development of reciprocal apprenticeship models that are more akin to the dynamic of day to day learning that young people who are eager to learn follow. If you took the salary of one new teacher in each school and spread it among the students who excel in teaching their peers you would create a new generation of students empowered to learn and teach, and infuse these students with income, however modest. Well, this is my suggestion to the conundrum of the teacher shortage. I would value your feedback.

Warm regards,

Jan

Dear Jan,

My name is Boris, I'm from Gabon. I found you posting very interesting. I am writing an essay on ICT-based education, and I would like to quote you in it with this saying of yours: " The teacher standing in front of the class is archaic and based on power and conformity–not learning". May I have more details of your:

full name, profession and location?.

On the other hand, i would like also to keep in touch with you through emails (first and phone, why not, lol ) to exchange views. I have a project and your posting gave me food for thought.

Thanks.

Hello Boris, yes, by all means feel free to quote me. I would be very interested in hearing about your work–please share. Warm regards,

Jan