Mobiles For Teaching And Learning: Translating Theory into Practice

This article is an adapted excerpt from a full paper that was presented at the mLearn 2012 conference in Helsinki, October 14 2012. “Mobiles For Teaching (And Learning): Supporting Teachers With Content And Methods For Reading Instruction”. The full paper will be published in the forthcoming conference proceedings.

What is m-learning? Is it you or is it your mobile?

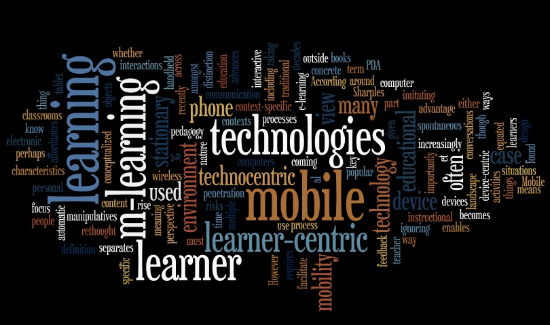

Mobile learning (m-learning), though increasingly popular given the rise in mobile phone penetration and advances in wireless and 3G technologies, has been part of the education landscape for decades. During this time the term has been conceptualized in many ways, from a technocentric perspective, meaning the use of handheld electronic devices for educational activities in or outside of classrooms, to more learner–centric “processes of coming to know through conversations across multiple contexts amongst people and personal interactive technologies” (Sharples et al. 2007). The key distinction is whether the focus is on the mobility of the learner, or on the mobility of the device. In the device-centric view, mobile learning is often equated with the mobile phone, the PDA, or more recently, the tablet computer.

However, these technologies are often used in situations where the learner is stationary, or perhaps mobile but ignoring the environment around them, in which case the content and pedagogy risks imitating the same thing that was used on stationary computers. In the learner-centric view, what separates m-learning from e-learning is the spontaneous nature of learning and the way in which learning becomes context-specific through interactions between the learner, the device, and the environment. According to this definition of m-learning, many things can facilitate the learning process, including books or other concrete manipulatives or found objects, but importantly, the technology enables communication between learners, learner and teacher, or other means of automatic feedback. In either case — technocentric or learner-centric — m-learning requires that traditional instructional design of educational technology must be rethought, taking advantage of the specific characteristics and affordances of the mobile technologies.

Why m-learning?

A 2008 review of m-learning for teacher training noted that the benefits of m-learning, as described in the literature, were the convenience and immediacy of learning that the technology enables; and the motivation that comes from being empowered to take learning into one’s own hands (Pouezevara and Khan, 2007). These benefits are still relevant, though with the rapid changes in technologies and data networks, a few additional benefits have emerged. JISC, in their more recent m-learning InfoKit (JISC, 2012) have compiled a list of 18 “tangible benefits” of mobile learning.

These can be categorized into four main themes: accessibility (access to learning opportunities, experts/mentors, other learners); immediacy (on-demand learning, real-time communication and data sharing, situated learning); individualized (bite-size learning on familiar devices; promotes active learning and a more personalized experience); and intelligence (advanced features make learning richer through context-aware features, data capture, multimedia). From this perspective it is clear that m-learning today—at least in the developed world where it is possible to be ‘always connected’—is about the mobility of the learner, not about the device.

In the developing world, however, m-learning is not only about having “just the right content, on just the right device, for just the right person, at just the right time” (Hodgins, 2002), but also having all of this at just the right cost. With the staggering increases in ownership, mobile phones and handhelds have become essential parts of daily life for youth and adults alike (see this recent study), and an ever more important common denominator for reaching potential learners.

Therefore, globally, the question is no longer whether learning should be mobile, and which devices will make it so; rather how to develop and deliver mobile content that is effective, efficient and engaging. This goes far beyond eLearning, or simply delivering the same content on a different—a mobile—device; instead, the mobility of the learner, supported by a mobile device, opens up new prospects for learning altogether. This suggests a number of new ways to think about the “m” in m-learning: microlearning, multimedia learning, and mastery of learning[1].

The purpose here is not to add to or confound the different definitions of mobile learning, but rather to move the conversation away from broad notions of mobile learning where the term itself evokes only a medium of delivery, and not pedagogy[2]. Alternatively, m-learning can describe new ways of designing and implementing mobile learning from a pedagogical perspective. Strategies for developing mobile learning content must draw on the features of the device, connectivity, user ability, and learning objectives.

m-Learning = microlearning.

Microlearning is a theory of instructional design that suggests that people learn more effectively if information is delivered in small units that are easy to understand and apply (Habitzel, et al. 2006). As a teaching method, it implies breaking content into small teaching units and delivering them with a modified pace and timing (Edutech Wiki, 2012). The characteristics of m-learning—using smaller, connected mobile devices independently of classroom time, space, and teachers—lend themselves to a microlearning perspective of content development and delivery. First of all, delivering only small units of learning at once is the most feasible way to deliver any content at all on many mobile devices—especially in developing countries—given bandwidth limitations, cost of data transfer, and screen sizes.

From a pedagogical perspective, the timing of such micro-units of learning is important for encouraging ‘anytime, anywhere’ learning, and situating it within the environment where learning will need to be applied later. This concept of situated, just-in-time microlearning enabled by mobile devices is demonstrated by widespread examples of “apps” and programs such as mobile “coaching” services, which deliver daily messages about health and lifestyle to subscribers on their mobile phones. The sequenced and situated nature of the messages appears to encourage behavior change more than one-off classes[3].

The intersection of mobile learning with microlearning therefore implies that we must revisit training programs and their content and attempt to sequence and deliver that content more appropriately into its microunits. This must be deliberate and careful, to avoid trivializing the content as Vosloo cautions against an earlier EduTech debate article.

m-Learning = multimedia learning.

Multimedia for teaching and learning is also not a new concept, nor does it apply exclusively to mobile learning. The use of video for microteaching and broad instructional delivery has been common practice for many years in teacher training programs in developed and developing countries. Now, mobile, digital recording devices and portable projectors have made this method more accessible to teachers and teacher trainers in developing countries. Short video and audio can be transferred via mobile data networks, or transferred manually between feature phones further increasing the possibilities for effectively using video for individual and peer learning.

“Flipped” classrooms around the world have emerged out of the ability to view video and other advanced learning content independently outside of the classroom, with the teacher acting more as a facilitator than a lecturer and thus increasing classroom time dedicated to practice and active engagement of content. New advances in technology and increasingly affordable devices are changing the way traditional interactive radio instruction is being delivered, making it more interactive and truly ‘multi’media by combining radio broadcasts with phone-in or text messages to the show, for example. It can also be more mobile now that radio broadcasts can be recorded and stored on digital media players.

For example, an m-learning pilot in Malawi tested the feasibility of using a portable MP3 player to support pre-service teachers in an open and distance learning training program. The devices combined text display, audio and video playback, FM radio, and photo and video recording all in one low-cost device. The program enabled teachers to review 5 weeks of lessons and required them to create audio-visual materials as part of the program. (Carrier, 2011). Augmented reality and context-aware applications for smartphones or tablets allow learners to engage with the environment around them through video and photo capture, and manipulate these to apply mathematical or scientific theory to real-world situations.

Therefore in addition to being an appropriate pedagogical model on its own, multimedia teaching is also a form of microlearning, if delivered in short, strategic bursts. This type of teaching is particularly relevant to teachers in developing contexts who are often undertrained and inexperienced. Approaching m-learning from the perspective of mobile multimedia opens up possibilities of ‘virtual mentoring’ and rich multimedia distance learning as an alternative to traditional correspondence-based forms of open and distance learning that are still common in low resource environments. It allows us to take learning out of the classroom and be less dependent on static textbooks to explain complex, multi-dimensional concepts.

m-Learning = measurement of learning.

It is widely noted that improving instructional quality depends on providing teachers with the training, skills and resources they need in order to improve learning and achievement. What is often overlooked in this basic theory of change (e.g., training leads to change) is that teachers need to be aware of the quality of their own instruction and gaps in their children’s achievement in order to address those gaps and apply strategies that work. For Guskey (2002) it is not just a matter of addressing specific skills gaps for certain children—although this is an important reason to do frequent (formative) student assessment; seeing evidence of change is critical before teachers will adopt new teaching strategies. There are many ways to carry out student assessment, from short lesson-level quizzes to larger standardized tests; any such assessments can be successfully conducted without technology.

The challenge is making use of the results in an effective and efficient timeframe. The use of measurement for results requires that the results be accessible and easy for the teachers and those who supervise them to use to inform their own instruction and communicate results with parents and other stakeholders (Strigel, 2011). Too often, results from national standardized tests remain at the national level, and teachers rarely get the feedback on performance, much less feedback that is more specific than classroom averages.

The same technologies that allow us to introduce new forms of content delivery and learning can also change the way learners are assessed. In distance or mobile learning environments, assessment is likely also going to be mobile. However, traditional teaching and learning environments like those often encountered in low-resource classrooms can also benefit from mobile forms of mastery checking that allow instantaneous viewing of individual learners’ results, aggregating results over time, and presentation of results and progress over time in simple, easy-to-understand graphics. The power of mobile computing allows sophisticated ‘data-mining’ or ‘data-analytics’ to provide simple insights on student performance and the teaching strategies that got them there.

Summary.

Chris Dede of the Harvard Graduate School of Education provides a useful analogy when he cautions against education technology simply “putting old wine in new bottles” (Dede, 2011); he envisions, instead, that we develop “new wine” and even allow the “bottle” to disappear as we access learning without the constraints of classroom time and space. By exploring some new definitions of “m-learning” I hope to come closer to identifying what the new wine and the new bottles might look like, and how to deliberately develop content for mobile learning that goes beyond repackaging traditional content for mobile devices. I look forward to comments from the rest of the community on how m-learning is perceived and applied where you are, and how you approach instructional design for mobile learning.

References:

JISC mobile learning infokit: http://mobilelearninginfokit.pbworks.com/

Pouezevara, S. & Khan, R. (2007). Learning Communities enabled by Mobile Technology: A Case Study of School-based, In-service Secondary Teacher Training in Rural Bangladesh. Bangladesh Country Report. ADB TA6278-REG. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International.

Wayne Hodgins, “The Future of Learning Objects,” presentation at the Learning Objects Forum, Menlo Park, California, September 3, 2002. Cited in Wagner, E. (2005). Enabling Mobile Learning. EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 40, no. 3 (May/June 2005): 40–53. http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/enabling-mobile-learning [Accessed 14 October 2012]

Habitzel, K., T.D. Märk, B. Stehno, and S. Prock. (2006). Microlearning: Emerging Concepts, Practices and Technologies After E-Learning. Proceedings of Microlearning 2005 Learning & Working in New Media. Cited in Fozdar, Bharat Inder and Lalita Kumar. 2007. Mobile Learning and Student Retention. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. Vol. 8. Issue 2. Alberta. Available: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/ irrodl/article/view/345/916.

Carrier, C. (2011). Alternative Technology Pilot for ODL—Using an MP3 Player for Numeracy Training. Short-Term Technical Assistance Report by Seward Inc. Submitted to USAID Malawi Teacher Professional Development Project (Creative Associates International/RTI International).

Guskey, T. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice. 8(3/4).

Dede, C. (2011). Mobile learning for the 21st Century: Insights from the 2010 Wireless EdTech conference. http://wirelessedtech.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/ed_tech_pages.pdf[Accessed 9-30-2012]

[1] A reasonable additional ‘m’ would be “motivated learning” (Gorton W., Personal Communication, 2012). Experience suggests that using technology and being in control of one’s own learning through m-learning approaches can increase motivation and engagement. This is particularly true for game-based learning which is increasingly available on mobile phones. This 4th ‘m’ will not be covered specifically in this paper, however.

[2] Whereas “e-learning” as a term clearly links to the electronic medium, and recalls other related terms for computer- and web-based applications such as e-mail. Similarly “distance” learning clearly refers to learning that is removed from the instructor or classroom, but independent of any specific pedagogical medium. The term “m-learning”, unlike these two predecessors, is ambiguous enough to make us wonder are we talking about mobility and learning on the move, or are we talking about learning with mobile devices, such as mobile phones.

[3] See http://www.text4baby.org/index.php/news/180-sdpressrelease

I saw this presentation in Helsinki. Very informatuve. I gave a prentation in the Doctoral Consortium at mLearn 2012 on a similar topic, called QR Cache: Brindging mLearning Theory andd Practice, which will also appear in the forthcoming proceedings. The QR Cache wiki is at http://qrcache.pbworks.com

I highly recommend that anyone interested in mLearning check out the full proceedings!