Worldreader is leading a reading revolution in the developing world

In April of this year, I wrote the following in the Educational technology Debate post eReaders will transform the developing world – in and outside the classroom:

“If Worldreader’s experience so far is any guide, e-readers are set to transform the developing world, both in – and outside the classroom. But this change won’t be driven by e-readers by themselves – it will be driven by human curiosity, ever-increasing connectivity, enlightened self-interest, and a gentle push from organizations like ours.”

Having just returned from visiting Worldreader’s program in Ghana, as well as looking at the recent trends in e-reader pricing, I believe this more strongly than I did six months ago. The planets are coming into alignment for a true revolution in the way the developing world reads, and consequently for the way students learn.

Worldreader’s impact

First, a bit of background. Worldreader is working to put books into the hands of one million children in the developing world by 2015. Working with USAID and a private aid agency in Ghana, we’ve put e-readers into the hands of hundreds of children, and then loaded them with local text- and story-books, as well as international fiction.

In total, we have distributed over 80,000 e-books in the past nine months. It’s worth thinking about that number for a second, because it’s staggering: it’s the equivalent of two-and-a-half shipping containers. In our case, they were all delivered wirelessly, using the same cell-phone infrastructure that is becoming more ubiquitous every day. (Ghana’s Daily Graphic reports that mobile phone penetration stands at 81%.)

What’s even more interesting is that number doesn’t count the thousands of books that the children and teachers have downloaded themselves over the same period. Just looking at the four-month period from May-August (much of which was over vacation), we logged downloads of 1,301 free book downloads and samples (one popular book: No Good Deed), 1,036 educational game downloads (including Thread Words— I played it with a few students while I was there), and 92 subscription downloads for free trials of newspapers and magazines.

Remember that all of this is against a context of a severe lack of books. According to SACMEQ, half of the classrooms across six countries studied in Sub-Saharan African have no textbooks at all, because of cost and logistical issues. And as Michael Trucano notes in his World Bank blog, ”Only 1 out of 19 countries studied (Botswana) ha[s] adequate textbook provision at close to a 1:1 ratio for all subjects and all grades.” Books just aren’t getting to Sub Saharan Africa.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that when we put books into students’ and teachers’ hands, they read them. Two weeks ago I met a girl named Patience who had read 90 books in the past six months, and she wasn’t alone: children across the classroom had devoured 50, 60, or 70 books. In fact, on average children are now spending 50% more time reading than those in control schools, and primary students’ test scores have increased some eight points more than those of students in comparable schools.

While everyone knows that test scores fluctuate wildly over the short-run, it’s clear that these children are reading more than ever before, and the effect is almost palpable. (The USAID observer who dropped in on our program admitted he’d never seen young children so engaged in reading… and he’d been a teacher for 10 years before joining USAID.)

Interestingly, the “reading effect” wasn’t limited to students. The English teacher at Adeiso Presbyterian Junior High School teaches one class with e-readers and one without. He admitted to me that he felt a bit lazy (his words) in the e-reader class, because the students had already competed all the reading. Cynthia, a primary-school teacher, proudly showed her collection of religious and inspirational book samples that she had collected. And parents we surveyed reported that their children were reading to their siblings after school.

Local publishers embrace e-readers

Equally interesting is how publishers are responding. Local publishes see this as an opportunity to expand their market dramatically, both within the developing world and outside. As Elliot Agyare of Ghana’s SMartlin Publishing has said, “I’d be more than happy to drop my prices to [50 cents] if I could sell on hundreds of thousands of e-readers.”

Meanwhile, international publishers have taken note: Worldreader has obtained the rights to use books from Random House (including the Magic Tree House series), Penguin (including four of Roald Dahl’s books), and more in our program for free. For international publishers, it’s an inexpensive way to help the developing world become active readers.

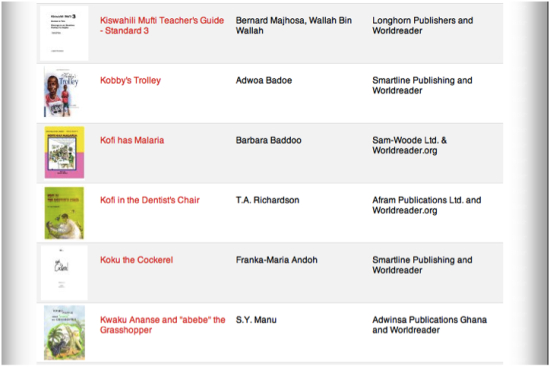

A selection of the 230 books in Worldreader’s program.

Overcoming issues – real and perceived

The other interesting news is what’s not happening: theft hasn’t been a problem. Of the 500+ e-readers in circulation in Ghana, we’ve lost a grand total of three over the past six months. And a boy came up to me while I was there and reported he thought he’d seen one of the missing units in town— we’re tracking it down. The communities have been magnificently unified in working with us to see our work together succeed.

Of course, there’s less-good news too: e-readers still break too often (though Amazon has done good analysis on why, and is helping with solutions, plus we’re now using different cases and rolling out an incentive program to keep the Kindles unbroken). It’s not always easy to keep up with the kids’ appetite for new local books: it takes a fair amount of effort to maintain momentum with local publishers who have lots of issues to juggle. But these issues get easier with scale, as we build demand for more hardware and books.

At this point, most observers will be thinking two things: the program, though early, seems to have some traction, but the cost must be high. And there’s no doubt that e-readers are still too expensive to catch on widely in the developing world. But recent evidence suggests convincingly that prices are coming down fast: Amazon’s least-expensive Kindle is now $79, as compared to $399 three years ago. Of course, that’s for an advertising-supported, WiFi only model.

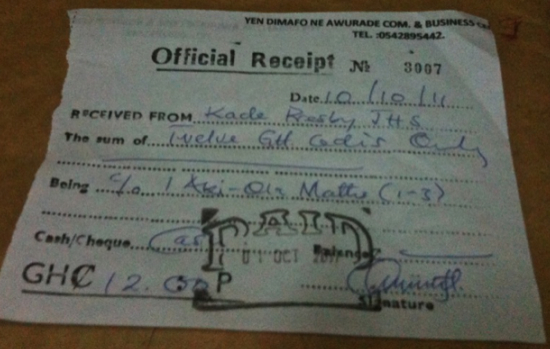

Still, if you assume the existence of a $50 e-reader, and spread that cost over 5 years, you’re approaching costs that many parents and governments can bear. In fact, the enclosed picture of a receipt is for the purchase of a single math textbook that a headmaster purchased on behalf of one of his teachers. The cost of the book is 12 Ghanaian Cedis (about $8.00) for only one of about eight required textbooks across the curriculum.

Expanding past Ghana

But perhaps the success we have seen so far is specific to conditions in Ghana, or to the people involved in this pilot. Well, early indications from our work in East Africa suggest otherwise. This past weekend, Al Jazeera aired a piece on our work in Kenya’s Rift Valley, and the results are largely consistent with what we’ve seen in Ghana.

What’s remarkable is that after the initial set-up, content load, and training, much of the on-going work has been in the hands of local teachers. We believe this is a fundamental ingredient to the success of any ICT program: teachers have to embrace the program, and for that to happen, implementation needs to be easy. In the case of e-readers, this is the case: the technology is simple to use, and in the end, incorporating it into the classroom feels familiar. After all, they’re really just books.

Worldreader is just getting started. The technology we’re using is still early in its development, and prices are still high. But the trends are all headed in the right direction to allow us to achieve something unimaginable before, potentiall allowing entire countries to skip the paper stage of books in favor of e-books. If that happens, we’ll unleash a wave of creativity that’s unlike anything we’ve seen before.

Hi David,

Thanks for bringing Worldreader to my attention! This is a fascinating initiative, and I think that the enthusiasm and increase in reading you've observed really speaks to how access to books has the potential to fundamentally alter children's educational experiences.

I especially appreciate that you spent a good deal of time addressing potential critiques, I think that that your responses to concerns about total cost of ownership were well thought-out and fairly realistic.

I have a couple of questions related to TCO–they're are more hypothetical and long-term, as I'm particularly interested in what happens after this project stops (or scales up beyond) being fully supported by external funds:

1) Have the parents/teachers demonstrated the financial ability to make the initial investment in purchasing an e-reader? My thought is that, even if the price drops to $50 per device, a low-income family may not have the funds/savings to invest this amount all at once, whereas the incremental cost of buying one book at a time may be more feasible, despite offering fewer benefits in the long run. From your experience on the ground, what are your thoughts on this? Also, you mention "spreading the cost [of the device] over 5 years" as a potential solution and I'm wondering what you mean by that?

2) What about the cost of shipping? Depending on where the devices are coming from–and how accessible a place they're going to–shipping could be a significant expense. If a $50 e-reader is, say, $60 with shipping, even that small amount might put it out of reach for the target demographic. How might this might this impact the project's financial model and local uptake, once people need to purchase the devices themselves?

3) What about maintenance of the devices? You mentioned that e-readers still break too often and, while I'm sure more durable models will be developed in the not-too-distant future, technical issues are bound to arise. Would the project (or e-reader company) provide technical support? If not, how would this impact the sustainability of the project? If so, would this be local or remote? If local, how would the technicians be trained? If remote, where would it be based and how would people access it? In both cases, how would this impact that TCO?

4) Would this initiative have to be adopted school-wide? If not, it's likely that existing socio-economic divisions would impact families' abilities to purchase these devices and that, as a result, these divisions would be replicated in patterns of ownership among the students and teachers. This could possibly heighten existing educational and other social inequalities, which I'm sure would not be in line with the project's intentions! How do you think these challenges might be avoided or addressed?

Thanks for taking my questions! I look forward to learning more about Worldreader's work as the project progresses.

Best,

Samantha

Hi, Samantha,

Thanks for your interest and your great questions! I'll take them one-by-one, and then we can see where this goes.

1. On the payment for the devices: that's one of the areas we're most interested in testing next. When I was in Ghana two weeks ago, we assembled a group of parents to talk about the program. At one point we asked them what they'd be willing to pay. Of course, their first reaction was: Wait, what? But very quickly they moved tto: You know what– we understand this can't be free, and while we don't think we'd be in a position to pay the full cost, we would be happy to speak with other parents to help them see why it's worth paying something. To me, that was super-powerful: nobody ever volunteers to pay for something that's free, but if you see evidence that folks are willing to champion the cause, that means a lot.

Our next step in Ghana includes a segment of our pilot where we'd test this. For what it's worth, I think the right model is going to be that governments subsidize the hardware cost and pay for an (inexpensive) set of textbooks. Parents will need to chip in on the rest. But this could be spread over years: to answer the other part of your question, if the device lasts for 5 years, you can think of this as a $10/year cost, split between governments and families.

I know this is speculative at this point, and ignores factors like interest. But the signs are positive, and like any good organization, we want to learn more by testing.

2. The cost of shipping is fairly low– less than $5.00/device, and that's without any real negotiation on our part. Think of it this way: it's should resemble the cost of shipping roughly 1 hardback book. But it's better than that, because a lot of the hidden costs of shipping are logistical costs: getting the right item to the right person. In this case, you're shipping identical items, then "personalizing" them with books on location.

3. Maintenance is another issue we're working on pretty actively. Today, when there are problems we ship them back for analysis and replacement. But we see a time when some repairs can happen locally, just as is the case with cell-phones. In fact, we're doing a little unofficial experimenting ourselves– here's a "FrankenKindle" picture from a few weeks where we took two broken e-readers and made one: http://pic.twitter.com/EC1v25or

To me, maintenance is one of those great problems to have, because it shows that the devices are getting used heavily. As we scale up, it only creates more local opportunities.

4. Another great question: "does the initiative have to be adopted school-wide?" Our experience so far is that it's very helpful to deploy it across an entire classroom, because of the step-change it has on the way the teachers work with the class. (It also helps enormously that new students who enter can rely on a large critical mass of existing students to learn from.) We deliberately not blanket our schools at first in part so we could study the effects this had on other classrooms– not surprisingly, there's an enormous amount of interest from the other classes, which actually can help teachers a bit– gives them something to aspire to.

On the issues of equity, we've addressed these so far by a) talking to the whole school a lot about the responsibility of everyone to support the program so that we can expand, and b) starting a "Vacation Reading School" program this summer that put our e-readers in common areas for kids to share. We weren't sure what to expect, but once ago were positively surprised: over 150 students dropped in over 25 days and 21 attended 12 days or more (many of whom were not Worldreader students.)

We have decided to continue this so that non-Worldreader students can continue to read. It's important to note that this was all in the context of hundreds of kids already being familiar with the devices and the books on them, but it gives us a lot of hope.

If you'd like to know more about that program, we've just written a document that summarizes it. I think you're the first to see this outside of Worldreader– I know I just created the link this very moment :).

http://bit.ly/WRVschl

That's it for me now. Feel free to ask more questions, or write me directly. I hope this has been interesting to others as well!

— David

Hi David,

Thanks so much for your interesting, detailed reply! A few follow-up thoughts for this thread:

1. I think it's great that you've already started thinking about and approaching parents about the issue of payment. It's certainly positive that there is a recognition of the benefits of investing in the program, and enthusiasm about promoting it to others. I think that trying to mirror the financial approach to purchasing traditional textbooks makes sense (both in relation to the device and the shipping costs), which it seems to me is what you're proposing to do with the government-subsidized model.

All in all, I'm very interested to see how your approach evolves and how the related segment of your pilot in Ghana plays out practically!

2. Love the "FrankenKindle"!! I also think that you're really on to something with supporting repairs happening locally–I see a real opportunity here to build capacity and create jobs in the communities with these programs.

3. Thanks so much for sharing the "Vacation Reading School" report! I think that this is an excellent way to make the technologies available to other students before the project scales up. You've also clearly put a lot of thought into addressing issues of equity and I also agree that it makes sense, in terms of M&E, not to blanket entire schools in order to have a control.

I guess I'm mostly curious as to how issues related to equity change and manifest over time, as the projects continue, more classes are integrated and student turnover begins when older kids graduate and younger kids join the program–but I suppose these are things that only time will tell.

Thanks once again for your thoughtful reply. Looking forward to following how the WorldReader project progresses!

–Sam

I am a big fan of the e-Reader idea for several reasons. On the purely technical side, as a single-purpose device it is much easier for novice end users to understand and operate. It is also much easier to support as the ICT manager. Initial purchase costs are significantly less than other multipurpose technologies as well.As a bonus, by getting content into a digital format, the e-book reader can spur adoption and consumption of digital content across all digital platforms – from eReaders to laptops to desktops and beyond. I think Worldreader's ability to get publishers on board with e-books may be the real long-lasting ICT achievement.